Jo Boaler, a professor of mathematics education at Stanford University, is not new to criticism of her work turning ugly. Boaler champions a reformist approach to teaching maths, arguing that strategies that emphasise reasoning over memorisation lead to more equitable outcomes. When she first moved to the US from Britain in the late 1990s, she was warned that her research would anger defenders of traditional methods. Backlash from some colleagues – including accusations of “scientific misconduct” that the university dismissed – grew so personal that she briefly moved back to the UK.

Back at Stanford two decades later, Boaler was tapped in 2019 by the California department of education with four other scholars to rewrite the state’s mathematics pedagogical framework, a non-binding guide seeking to help educators improve outcomes “for all students”.

That made Boaler a target once again. This time, the debate moved beyond the so-called “math wars” to become another battle in a newer conservative-led war over diversity and inclusion. Because her research focused on outcomes for students of all demographics and backgrounds, Boaler’s critics branded her as “woke” and attempted to delegitimise her work. Tucker Carlson, Ted Cruz and Elon Musk came after her. Opponents of her research sought to ruin her career, she says.

The campaign against her harmed her reputation and took a personal toll. “The physical threats to my family were obviously the worst aspects, but erroneous and unfounded attacks on my work are physically and mentally draining,” she said.

But the campaign against Boaler was hardly an isolated incident. Instead, it followed a well-tested playbook, which, since the 2024 resignation of the former Harvard president Claudine Gay over plagiarism accusations, has been increasingly wielded against women, scholars of color and others perceived by the right as progressive.

“Most institutions, and even most individual scholars, aren’t fully aware of what’s been happening,” said Rebekah Tromble, a professor of media and public affairs at George Washington University. “And how this is ratcheting up and what could come for them.”

Rufo’s playbook

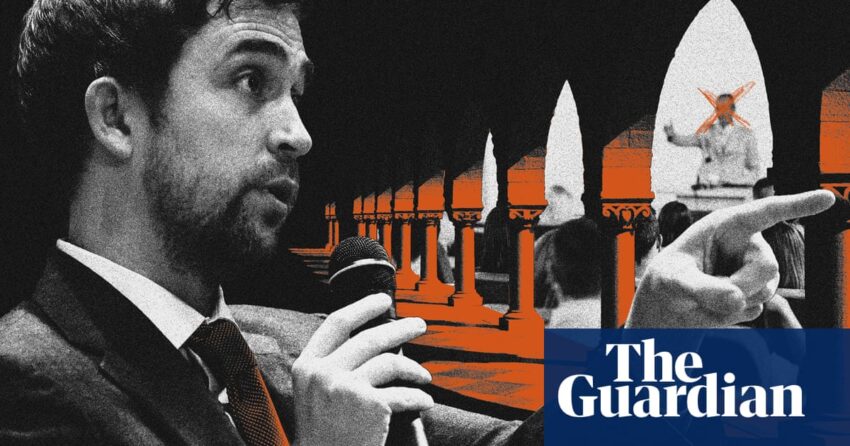

Recent, organised attacks against scholars have often involved accusations of academic misconduct published in rightwing media, social media campaigns to make the allegations go viral and pressure on universities to disown their faculty. These kinds of campaigns have been pioneered by Christopher Rufo, a conservative operative who first made a name for himself as a crusader against “critical race theory”, an academic approach examining the role of systemic racism in society.

Rufo first surfaced the plagiarism allegations against Gay just six months after she made history as Harvard’s first Black president, and shortly after she came under fire during highly charged congressional hearings on accusations of campus antisemitism. He called the campaign to force her out of her job a “successful strategy” and “team effort”.

While he gleefully took credit for Gay’s demise – when she quit, he posted the news with a comment, “scalped” – Rufo spoke of the campaign against her as a model he hoped others would emulate. It involved, he said, “varying degrees of coordination and communication” with media figures, conservative donors and politicians. (He was not involved in the campaign against Boaler.) “I’ve run the same playbook on critical race theory, on gender ideology, on DEI bureaucracy,” he told Politico magazine. “This is a universal strategy that can be applied by the right to most issues.”

Rufo’s comments following Gay’s resignation were a candid acknowledgement of a growing phenomenon scholars have increasingly warned about, involving sustained campaigns by conservative activists seeking to undermine the legitimacy of higher learning institutions they view as the root of “woke”, or liberal, politics. It’s a movement that has been embraced by many in the Republican party, including Donald Trump, who has made diversity and equity initiatives a primary target and who has promised to end “the scourge of DEI”.

Rufo declined to answer the Guardian’s questions about these campaigns or his role in them.

“Scholars have been screaming from the rooftops: ‘This is a playbook,’” said Tromble.

Alarmed by the growing trend, in September she launched the Researcher Support Consortium, an online tool for scholars facing harassment or intimidation that seeks to fill the gap left by academic institutions, which she says have been slow to address the problem.

Since publishing the toolkit, Tromble has heard from “hundreds of scholars from across more than a dozen disciplines who have either experienced harassment or know colleagues who have,” she said. Since Trump came into office, she says she personally spoke with “over 200 scholars, administrators, and representatives from scholarly associations”, she added. “Outreach has skyrocketed.”

Those coming under attack are often surprised to learn that their own experiences follow a tried mechanism and come at a high professional and personal cost. In some cases, scholars have been forced to scrap their public profiles or seek police protection.

‘Weaponising’ plagiarism accusations

Isaac Kamola, a political science professor at Trinity College, documents rightwing efforts to undermine higher education. Both he and Tromble noted that while earlier campaigns came in response to statements made in class or online, they now are increasingly aimed directly at scholars’ work, including through accusations of plagiarism or other research misconduct.

“That general narrative about higher education being hostile to conservatives, being overly woke, that field had already been plowed,” Kamola added. “But Chris Rufo really just poured gasoline on that fire, and turned it into a terrain of real political success that the right, donors, rightwing activists, and thinktanks like the Heritage Foundation and Manhattan Institute can really double down on.”

The Manhattan Institute, where Rufo is a senior fellow, has published several stories accusing faculty of plagiarism. (Rufo was formerly a fellow at Heritage, the thinktank behind the rightwing Project 2025 blueprint.) One of the stories he wrote for City Journal, the institute’s magazine, shows paragraphs of a scholar’s work apparently marked up by plagiarism detection software. In another, he writes openly about having “tasked my researchers with investigating potential plagiarism by Harvard scholars”.

During the presidential campaign Rufo also accused Kamala Harris of plagiarising passages of a book she wrote in 2009 – with Harris’s campaign responding that the accusations were the work of rightwing operatives “getting desperate”.

But Rufo is not alone, Kamola noted: the Washington Free Beacon, another rightwing publication and the first outlet to publish misconduct allegations against Boaler, has dedicated an entire section to stories about “plagiarism”. Most of those articles are about Black scholars, while others are about deans working on DEI programmes; another is about a white scholar whose work focuses on racism. In the three months following Gay’s resignation, at least seven other scholars faced similar accusations, the education publication Inside Higher Ed reported last year. Six of them were Black, and three were Black women at Harvard. (The Harvard Crimson, the university’s student paper, called the attacks a “witch hunt” against Harvard’s Black faculty.)

Rufo’s own articles for City Journal also disproportionately target faculty of color, though Rufo has denied targeting Black women and said that he investigated scholars of “all racial groups” and that the results point to a “ponderance of plagiarism by academics who specialized in ‘diversity’”. The Guardian reached out to a range of professors from different backgrounds for this story; most did not agree to speak on the record.

Gay’s resignation prompted much debate about plagiarism – with one scholar Gay was accused of copying from dismissing the conduct as “trivial” and others noting that there is little consensus about what constitutes plagiarism.

Because plagiarism is not “cut-and-dry”, it should be investigated and adjudicated by committees, Kamola said.

“The Washington Free Beacon and Rufo instead want to litigate these issues in the court of public opinion,” he said. “And then, of course, when one set of political interests builds an infrastructure to weaponise plagiarism accusations, the result is that only certain people are subject to these investigations.”

‘A political attack’

As the campaign against Boaler, the Stanford professor, picked up, Tucker Carlson in 2021 accused her of “infusing social justice into math”. Opponents of her equity-focused approach called on academic journals to retract her publications, edited her Wikipedia page, and lobbied conference organisers and grant funders to distance themselves from her work. The attacks against Boaler grew so intense that she had to change her phone number, while campus police started surveilling her home.

Then last March, someone filed an anonymous, 100-page complaint with Stanford accusing Boaler of 52 instances of “citation misrepresentation”. “Our contention is that Dr Boaler has misrepresented the findings and/or methods of a number of reference papers,” the complainants wrote. “For her to erroneously represent that these papers support claims made in her work, when they do not, is a reckless disregard for accuracy.”

A story about the allegations published by the Washington Free Beacon was picked up by other publications, and shared widely on social media, including by high-profile figures such as Ted Cruz and Elon Musk, who wrote that she “undermined math education in California”.

While Boaler has the support of some within Stanford’s administration, the university still launched an investigation. They closed it in April, with a spokesperson saying: “The University has reviewed the matter and has concluded that no formal process is needed, and that the allegations reflect scholarly disagreement and interpretation.”

While Stanford cleared her, Boaler said the experience was “awful”, isolating and intended to intimidate her out of pursuing her work.

“They’re literally trying to block research evidence from going out,” she said of those attacking her work and that of other scholars. “And it seems to me that the academic community isn’t coming together around this, and protecting its independence.”

Sitting ducks

Tromble, of the Researcher Support Consortium, noted that while some university administrations have publicly defended their faculty, others have caved to outside pressure. She points to Stanford’s closure of a research observatory focused on misinformation that had come under attack from Republicans. (Stanford disputed that the observatory was being dismantled, saying that its work would continue “under new leadership”.)

Increasingly, she added, legislators have directly contributed to the climate of harassment, for instance by demanding universities turn over syllabuses referencing certain terms, setting up committees to review scholars’ work, and sending letters and in some cases subpoenas. Few universities, she noted, have forcefully pushed back.

“Even if there’s absolutely no basis to the claims whatsoever, they’re likely to sort of shrink back,” Tromble said of many universities. “And the scholars themselves are put on the defensive and brought into account to justify themselves, when in truth they’ve done absolutely nothing wrong.”

At times, the campaigns to discredit faculty have been fueled directly by legislators or university boards.

Last spring, Bethany Letiecq, a professor at George Mason University’s College of Education and Human Development, published an academic article about what she called “marriage fundamentalism”, a critique of the supremacy of the two-parent married family. The research was covered – and Letiecq says wildly distorted – by the College Fix, a conservative publication dedicated to higher education that quoted scholars calling her research “dangerous” and “terrifying”. The coverage was soon picked up by many other outlets, including Fox News.

Around the same time, another article Letiecq co-authored with the Harvard professor Christina Cross also came under attack, with Rufo leading the charge and accusing Cross of “plagiarism”. (Rufo was not involved in the original attacks against Letiecq.) Cross declined to comment, but Letiecq said the experience had been “incredibly traumatising” for her colleague. Harvard called the accusations against Cross “false” and “absurd”.

“As a scholar, your integrity is all you have,” Letiecq said. “And so when they go after the very core of your scholarship, and you don’t have the mechanisms to fight back, it’s a pretty powerful tactic that they’re using to silence faculty.”

In her case, the coverage led to the “onslaught of the typical harassment that faculty endure these days”, Letiecq said. People called George Mason University demanding she be fired. Parents Defending Education, a conservative group, published one of her syllabuses on an online list of classes they said were examples of “indoctrination”. Someone left a graphic death threat on her voicemail. The university gave her police protection, scrubbed her address from the internet, and installed a panic button in her office.

“My family felt threatened, my partner felt threatened,” she said, adding that she had to warn her children to be alert for people who may approach them. “The stakes keep getting higher.”

But while the administration supported her, Letiecq worries about influence from the university board. She points out that the board member Lindsey Burke directs the Center for Education Policy at the Heritage Foundation and authored the education section at Project 2025, which calls for the elimination of the education department. When the stories about Letiecq and her colleague went viral, Burke’s colleague at the foundation retweeted a story about her calling on the governor of Virginia, Glenn Youngkin, to “clean out GMU”.

Burke did not respond to the Guardian’s request for comment.

“The university talks about trying to defend academic freedom, but they’re at the whim of these boards,” said Letiecq, who played a recording of the death threat she received at a meeting with Burke and the GMU the board.

“We are totally under attack,” she added. “They have massive resources. And we’re like sitting ducks.”