It wasn’t supposed to be this way for Emmitt Martin III. He graduated from Bethel University in McKenzie, Tennessee, with a degree in criminal justice and played tight end and fullback on the football team all four years. Friends of Martin said he was a role model to his two younger siblings and regularly posted about his love for his young daughter on social media.

Martin told people that when he joined the Memphis police department in spring of 2018, he wanted to make a difference. He was a member of Omega Psi Phi, a historically Black fraternity whose founding principles are manhood, scholarship, perseverance and uplifting society. Martin’s policing performance evaluations show that he exceeded expectations in judgment, reliability and dealing with the public. Few would be faulted for thinking he’d have the safety of Black people in mind as he patrolled their communities. Even fewer would imagine he’d take part in the savage beating death of another Black man, an assault that even the police chief called “a failing of basic humanity toward another individual”, an act that was “heinous, reckless and inhumane”.

Martin joined the city’s crime suppression unit, Street Crimes Operation to Restore Peace in Our Neighborhoods (Scorpion), in the summer of 2022. The unit had been started the previous year with 40 officers split into four teams that patrolled “hotspots” in Memphis to fight the city’s surge in violent crime following the pandemic. The officers were specialized in name, and sanctioned by the city to bring down crime by any means available, but subsequent reports claimed they were young and undisciplined, and lacked training.

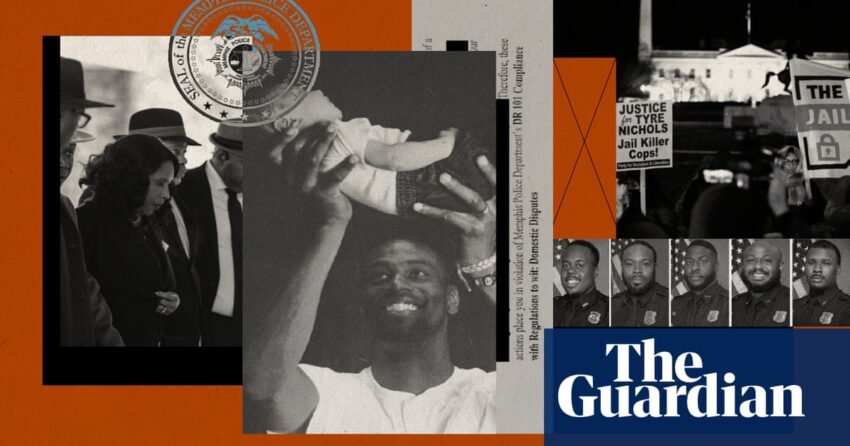

On 7 January 2023, Martin set out patrolling with four other Black police officers in Scorpion: Demetrius Haley, Tadarrius Bean, Justin Smith and Desmond Mills Jr. According to video footage from SkyCop, Memphis’s neighborhood surveillance system, 29-year-old Tyre Nichols was pulled over by Martin and Haley at around 8.24pm.

Hours of video have been released to the public, except for the few minutes that document why Nichols was pulled over. Officers initially alleged Nichols was driving recklessly, an allegation for which the Memphis police chief has said there was “no proof”.

When the body-camera videos cut in, Nichols is already being dragged out of his car by Haley at an intersection just blocks away from Nichols’s mother’s house. Nichols attempts to comply with the officers’ commands, but their orders are incoherent and contradictory. They tell him to get on the ground as he’s already lying on the ground and to roll on to his stomach as they twist him towards his back.

Within one minute, Nichols is pepper-sprayed and tased before he breaks away to run for his life. Later, he is chased down by Bean in the Hickory Hill neighborhood blocks away from the initial altercation, now just feet away from his mother’s doorstep. Smith joins in to hold Nichols down. While Nichols is held on the ground defenseless, Martin yells: “Lay flat, goddamn it!” He then rears back and kicks Nichols in the head, almost slipping as his boot crashes through Nichols’s face. Nichols stumbles up on to his feet, while being restrained by Smith and Bean, and is beaten by Mills with a metal police baton. Smith and Bean then hold Nichols up as Martin cocks his arm back and punches Nichols in the head five times. Nichols’s body twists with each blow, before he falls again into the street. Throughout the three-minute beating, Nichols whimpers, moans and screams out for his mother.

As the assault nears its end and Nichols is restrained, Haley runs ahead of other backup officers and kicks Nichols in the head. Nichols’s hands are then cuffed behind him, and his limp body is dragged to rest up against an unmarked police car. Haley takes pictures of Nichols and texts the bloody images to six people.

More backup arrives, and as police mill about the scene, the Scorpion officers joke about their attack. “Man,” Martin says, “I was hitting him with straight haymakers, dog,” referencing the long, winding punch preferred by street brawlers who use their size to take down opponents.

Twenty minutes later, after a battered Nichols was interrogated about drug use before becoming unresponsive, an ambulance arrived and took him to the hospital. Doctors reported that Nichols’s muscle tissues had broken down from the severity of the beating. The next day, his liver and kidneys began to fail and his brain bled. Three days after the beating, on 10 January 2023, Nichols was removed from a ventilator and died. His autopsy report outlined his myriad hemorrhages and abrasions, concluding: “Cause of Death: Blunt force injuries of the head; Manner of Death: Homicide.”

The videos documenting Nichols’s beating were released to the public on 27 January 2023. Within a week, national confidence in police use of force dropped to a new low, and for the first time, half of white Americans believed police treated Black people worse, according to polls by ABC News and the Washington Post. The killing drew national attention to the Memphis police department, and the city is currently under investigation by the United States Department of Justice.

The five officers involved in the attack were fired days before the first videos were released to the public. They are currently facing second-degree murder, among other state charges, and federal charges on deprivation of civil rights. Their federal trial is set for 9 September with the state trial to follow the federal conclusion.

Martin pleaded guilty on 24 August to federal civil rights charges of using excessive force and conspiring with the other officers to cover up the assault. Prosecutors are asking for no more than 40 years in prison for his role in the incident. Mills pleaded guilty to the same federal charges last November and is facing 15 years in prison. Haley, Bean and Smith have pleaded not guilty and are taking their chances with the court.

The Memphis police department did not respond to requests for comment. Martin’s attorney declined to comment on this story. Attorneys for Mills, Haley and Bean did not respond to requests for comment. Martin Zummach, who is representing Smith, wrote in an email that “we will be giving no interviews unless and until an acquittal occurs”.

Nichols’s killing has served as a reminder for many that minor interactions between Black people and law enforcement can turn deadly. When the police are Black, the strength of institutional racism can run deeper than skin color. Officer diversity is often pushed as a method to reduce bias in law enforcement, but years of research show that the culture of a department and the race of the people they are policing are far more consequential in determining outcomes. Crime taskforces tend to turn their aggression against the disenfranchised poor and minority communities they purport to serve, regardless of the crime rate. Nichols was beaten to death in a low-crime, middle-income, Black neighborhood.

Even when people join police departments with the best intentions, the realities of working on the force, including its incentives and culture, can change a person. Amber Sherman, a local activist and former college acquaintance of Martin, said that she had been shocked to learn of his role in Nichols’s killing, because in her opinion, he never seemed violent.

Sherman stayed in touch with Martin through mutual friends and social media, but said she noticed the tone of his posts change the longer he was with the department. “He had fully drank the Kool-Aid about these anti-Black things about Black people,” Sherman said. “That they’re more likely to be criminals, that we have to surveil them, that him joining this special taskforce was necessary, and that he had to target these certain types of people because they’re hardened criminals.”

Despite all the promises made by politicians following Nichols’s death, measures to rein in the Memphis police department have been rolled back. In some ways, the city is further behind on policing reform than it was before he was killed. But this is nothing new for the Black residents of the city who have suffered through brutality for generations and continue to fight for a check against the police.

A vicious history

To understand the conditions that led to Nichols’s killing, one must first understand the history of policing in Memphis. The Scorpion unit was developed in a city whose culture of law enforcement has been so vicious in its treatment of Black citizens that it was instrumental both in getting the 14th amendment passed following the American civil war and, in more recent history, limiting the extent to which police can use lethal force.

Memphis was founded in 1819 as a center for cotton production and the slave trade, with enslaved Black people making up a large part of the population. Policing grew out of the slave patrols of the time, which sought to enforce the racial hierarchy by capturing enslaved Africans who attempted to escape to freedom. After the city was liberated from the Confederate army during the First Battle of Memphis in 1862, it became a beacon for fugitive slaves. Following Emancipation in 1865, freed Black people looked to build new lives there. The patrols formed the basis for the city’s uniformed police.

The city’s Black population swelled following the civil war. On 1 May 1866, tensions between Black men discharged from the Union army and white police officers erupted into an all-out brawl. Though the initial violence abated within hours, an 1866 congressional investigation report noted: “Then the police and posse commenced an indiscriminate robbing, burning and murdering.”

The white mob descended on the Black residents of the South Memphis neighborhood, and over the course of three days killed 46 Black people, shot 75 others, raped five Black women and killed two white people. They also burned 91 homes, along with four churches and 12 schools, among other atrocities.

The massacre galvanized a Republican party much different from today’s GOP to pass the Reconstruction Acts, which defined the formerly enslaved as citizens of the United States and established provisions to secure their integration into society. The party also ratified the 14th amendment, which gives equal protection under the law to all American citizens.

Throughout the next century, Black Memphians continued to fight for their place in white society. The activist-journalist Ida B Wells-Barnett fought for equality in the courts and documented the city’s terrorizing of Black citizens through lynchings in her self-published pamphlet, Southern Horrors, in the latter half of the 19th century. In the early 1900s, Robert Church Sr, a formerly enslaved man who became the south’s first Black millionaire, turned Beale Street and South Memphis into a mecca for Black people. He built a park, a playground, a concert hall and an auditorium, along with establishing the city’s first Black-owned bank.

But the police force was ever present, often acting as a check against Black advancement. In 1917, five years after Church Sr died, police used fabricated evidence to arrest a Black man named Ell Persons for the rape and decapitation of a 16-year-old white girl. Before Persons could be tried in court, he was abducted by a white mob thousands strong, with what is believed to have been the police’s tacit approval since the action was advertised in the city’s paper of record, the Commercial Appeal. Persons was taken to the site where the girl’s body was found, lynched, set on fire and then torn apart by white community members.

“The fact that they threw the head of Ell Persons down Beale Street was just a perfect example of how they wanted to repress the economic activity that Robert Church and others were involved in,” said Brian Kwoba, a University of Memphis associate professor of history and director of the school’s African and African American studies program. The lynchings continued in the years following Persons’ killing, with either the aid of law enforcement or their blind eye. In 1953, Church’s vacant mansion, which had symbolized Black advancement in the face of white oppression, was burned down under the order of the city’s mayor.

By the time of the civil rights movement, Beale Street and Memphis’s Black communities were labeled “hazardous” by government redlining, with vacant buildings marked for demolition under urban renewal.

The city’s Black citizens reached a breaking point on 28 March 1968, when a planned march with Dr Martin Luther King Jr and the city’s striking sanitation workers turned violent. During the riot, a white cop put the barrel of a sawed-off shotgun to a Black teenager’s stomach and pulled the trigger, killing him. Six days later, on 4 April 1968, King was assassinated on a balcony of Memphis’s Lorraine motel.

It is not commonly known that King’s family doesn’t believe that the man charged with the crime was the killer, and that King’s former lawyer spent decades interviewing witnesses and collecting evidence that the true assassin was a sharpshooter with the Memphis police. In 1999, a jury accepted a version of this theory and awarded damages to the King family, although repeated federal investigations maintain that King was killed by a rogue gunman.

Three and a half years after King’s killing, a 17-year-old Black boy was beaten to death in a ditch by Memphis police officers and county sheriff’s deputies following a joyriding incident and ensuing car chase. Seven white police officers and patrolmen were indicted after the killing, along with one Black sheriff’s lieutenant. An all-white jury found the men not guilty. Following the verdict, the county sheriff held a party in his office, and the Black lieutenant was promoted to captain.

The story of Black law enforcement officers killing Black Memphians didn’t end with the civil rights movement. Within a year of that jury’s acquittal, Elton Hymon, a Black Memphis police officer, shot an unarmed, Black teenager in the back of the head as he was fleeing the scene of a burglary, killing him. The incident made it to the supreme court, where Hymon testified that the boy had posed no threat to him, and the court ruled that police could not kill simply to prevent suspects from fleeing, placing a pivotal limit on the permissible use of deadly force. Decades after the ruling, Hymon told a local pastor that he had been given a hero’s welcome at his precinct after serving his mandatory suspension for the killing: “What I resented was the implication that after killing an African American, I was acceptable.”

As the Hymon shooting was working its way through the courts, a Memphis college student uncovered a vast network stretching back to 1965 that had been established by the Memphis police department to covertly surveil private citizens – predominantly Black, social justice and anti-Vietnam war groups. The ensuing lawsuit led by the American Civil Liberties Union resulted in a consent decree in the fall of 1978, forbidding the department from establishing another such network, which the department violated by surveilling local activists involved with Black Lives Matter protests in 2017.

Earle Fisher, a pastor whose name was on one of the so-called MPD “Black lists” for his community activism, said that “even in the face of death, danger, despair and dehumanization”, journalists and activists “have found ways to do some fantastic and beautiful things and thrive. But it’s always been with the shadow of a system that leverages its laws, and enforces its laws, inequitably on Black citizens in the city.”

‘People become their own oppressor’

Memphis today remains a major commercial hub, especially for FedEx, which moved its operations to the city in 1973 after Beale Street had become nearly abandoned and was purchased by the city. Tyre Nichols was employed at the city’s FedEx warehouse when he was killed.

Warehouse work is usually temporary or part time, according to residents; one of the few stable full-time jobs available to members of lower-income, Black communities is working for the police department. In an effort to fill the ranks, MPD officially lowered its qualifications in 2018 by dropping the need for secondary education, and some residents are concerned that former high school students can be hired shortly after graduating.

“You don’t have enough jobs for people that want to work, and one of the few jobs that you do have available is making people become their own oppressor,” Frank Johnson, a county school board member, said.

The history of a city critically influences the culture of a police department. Thaddeus Johnson was born and raised in Memphis, and served with MPD for nearly 10 years before moving to Georgia and shifting careers to become an assistant professor of race and policing at Georgia State University. Through his current work, he’s seen generational race-based trauma affect policing in complex ways in cities such as Tulsa, St Louis and Chicago, which draw significant recruitment from Black neighborhoods.

Black men and women may join a police department wanting to help their communities, Johnson said. But the “pain and trauma” of growing up in areas saturated by anti-Black messaging, combined with the adoption of departmental culture, changes them and “maybe noble causes haven’t played out in noble ways”.

The complicated subculture, he said, often manifests as fear between police and citizens, especially in neighborhoods that see the most violent crime. Memphis is one of the few major cities that has seen a post-pandemic rise in homicides, topping out at nearly 400 deaths in 2023, while the rest of the country has experienced substantial declines. Although homicides are down more than 17% in Memphis through the first half of 2024 compared with last year, the figure is still substantially higher than the first halves of 2019 and 2020.

“It’s a very adversarial vibe oftentimes between police and citizens that often have nothing to do with the actual officers or citizens in those situations (but rather) the history in Memphis,” said Johnson of Georgia State University. “People are angry in Memphis, and those things run deep.”

When Johnson was about to join the MPD, he said, he asked himself: “What the hell am I doing?” But he needed a job, and at the time it was either work for the police or go “sling boxes” at a FedEx warehouse. Johnson’s father was a preacher and despised the police; he grew up in Memphis during Jim Crow with “colored only” signs and police dogs attacking citizens. “Those things are embedded in him,” Johnson said. “And guess what? They were passed down to me.”

Considering this conflicted mentality, a department that incentivizes arrests and aggression, and a mainstream view that minority communities are dangerous and in need of justice, it’s not so surprising that the officers did what they did to Nichols.

“Nobody is immune from anti-Black messaging,” Johnson said. “Quit acting like diversity is a kind of panacea.”

Diversity alone is not the answer

Diversifying police forces is one of the oldest methods of police reform, in large part because people of color have historically been excluded from the field. But, as Johnson points out, minorities can harbor the same implicit biases as white people, and some of the most diverse police forces, such as the New York and Los Angeles police departments, have troubled civil rights records. Last month, Black and Hispanic NYPD officers were recorded beating a Black Latino man during a Dominican Day parade in the Bronx.

As the authors of a 2018 Harvard Law Review article wrote while unpacking the complicated phenomenon of Black police officers: “Does this mean liberals and progressives are wrong to argue for racial diversity? No. It means that if racial diversity is the only game in town we are in civil rights trouble.”

Studies on the higher diversity of a department leading to more equitable policing are mixed at best, according to Jennifer Cobbina-Dungy, a professor of criminal justice at Michigan State University. “It’s often touted as a way to reduce violence in urban neighborhoods and police killings of civilians, but the reality is that it’s like putting a Band-Aid on something that requires surgery,” she said. “We’re talking about a system that’s often imbued with structural racism, and so oftentimes it’s very hard for one or two officers to come in and make real changes.”

As the New York Times has reported, Scorpion was known for pulling over Memphis citizens in unmarked cars and wearing black balaclavas covering their faces, their aggression sanctioned by people at the top of local government. In the short time the unit was active, their abuses were myriad.

From her research and experience, Christy Lopez, a former deputy chief of civil rights litigation at the justice department and a professor at Georgetown Law, said that specialized units tend to follow the same arc: a rise in crime leads to community outcry, and politicians respond by forming a crime-suppression unit to get tough. The unit hits the streets and aggressively rack up arrests and drug busts. The low-hanging fruit gets picked, but the pressure to bring in arrests remains, so the units broaden their net in Black communities, leading to the residents feeling both overpoliced and underprotected.

The final phase for many crime-suppression units is falsified arrests, extreme violence and/or corruption.

“Memphis is pretty archetypal,” Lopez said. “One of the things I found so chilling when I saw the (Nichols) video and read more about the Scorpion unit is that it really is kind of old school in its approach to crime suppression and crime-suppression teams … We shouldn’t underestimate how hard it can be for police officers who got into this job thinking they’re doing a good thing, and then they’re just dehumanizing people day after day, and they start to tell themselves stories about why that’s OK.”

“It’s remarkable what humans can do along those lines. I’ve seen it. People think that these officers must have just always been pathological or sociopaths or terrible people. It’s much more complicated than that for most of them,” she said, adding that there is evidence that standard police training and the complexities of being a Black officer can lead to them being more brutal than their white counterparts.

Commenting on the brutality of the Tyre Nichols incident, one of Martin’s former friends who knew him before he joined the MPD said: “I think it was a huge indictment of police training, because the Emmitt we knew, the Emmitt whose little baby girl I’ve held, who we’ve broken bread with several times, whose mother’s funeral we went to, who I’ve helped work on cars whenever he had an issue, that’s not the same dude.”

‘You don’t ever think it would happen to you’

As the justice department investigation into the pattern and practice of Memphis law enforcement proceeds, Guardian interviews with more than 30 residents, activists and academics indicate that many people are skeptical that lasting change will result.

Soon after the first videos of Nichols’s beating were released, the city council passed ordinances that prohibited the use of unmarked police cars during routine traffic stops, such as for driving with broken taillights or expired registration tags. Residents are not seeing much difference, however, and it was revealed earlier this year that the former mayor never enforced the policies.

Progressive members of the community gained some hope when Paul Young, a former downtown city planner, edged out the Shelby county sheriff to replace the outgoing mayor, Jim Strickland. Young assumed his office in January, but it is uncertain what effect he’ll have on police reform.

Young promised to enforce the bans on low-level stops, but the Tennessee state legislature, with a Republican majority, reversed the city’s ordinances with a bill that eliminated Memphis’s ability to rein in the police. Nichols’s family met with Bill Lee, the Tennessee governor, in hopes of convincing him to veto the legislation, but he signed the bill into law despite their pleas on 28 March 2024. (Lee, Young and Strickland did not respond to requests for comment.)

Cerelyn “CJ” Davis, the first Black woman appointed as police chief in Memphis, who rolled out Scorpion, is still leading the department. After a city council committee voted in January to replace her, Young vowed in May to reappoint her as chief. She is currently serving as interim chief, and despite the Nichols controversy, she is still one of the highest-paid law enforcement officials in the country.

During the justice department’s first round of interviews with residents, held in a local church’s meeting space, Memphians vented their trauma. Many talked about abuse and harassment at the hands of Memphis police; some broke down in tears. There were no answers to their pain, and if history is any indicator, reform will be slow. The justice department has released scathing reports in cities such as Minneapolis, Baltimore, Chicago, New Orleans and Los Angeles after years of investigation, and those police forces still struggle with claims of discriminatory policing.

For Nichols’s family, nothing will erase the horror of what was done to their son and brother, the tall, slim skater who loved nature and photography. His sister, Keyana Dixon, was 11 years older than Nichols and said she used to think of him as her little baby doll when he was growing up.

“I don’t know what the last minutes of my brother’s life was like, but I know that he was hurt, and he was scared,” Dixon said. She said she sometimes has night terrors “because of the visuals of what happened, the audio, hearing my brother moan and scream … You hear about it all the time, but you just don’t ever think that it would happen to you. And that’s the cold part about it, because it’s going to continue to happen to people and families.”

Unlike the politicians, city officials and activists, Nichols’s family isn’t from Memphis, and they didn’t choose to be in the public’s eye. The family’s federal civil rights trial is scheduled to begin in March 2025, and family members have had to take turns speaking with the media with each new development to conserve their mental energy. Nichols’s mother has been racked with anxiety leading up to the officers’ trial, and Dixon has been trying to build up her courage to sit in the courtroom and listen to the rundown of events that led to her brother’s death, although she’s asked in advance to be excused when they play the video.

“The world has already seen us cry on TV. They’ll continue to see us cry on TV,” Dixon said. “I can’t even grieve in peace. But there’s no peace in this grieving, because we have to get up every day. We have to display strength, because there’s going to be a trial coming up soon.”

Regardless of the outcome, what’s happening in Memphis mirrors the nation’s larger struggles with policing. Data shows police killings accelerating, and this year is on pace to beat last year’s record. Diversifying police forces alone isn’t going to solve the problem, and the country should hope that the exceptionally savage killing of Nichols doesn’t signal a regression to historical norms.