Monique was three years old when a white man from the government came to her village and changed everything. Everyone came out to see him, including Monique, who, as always, was with her “little auntie”, a girl of nine who was also her best friend. Monique cannot recall what the man looked like, but she remembers how sad everyone was after he had gone. Her mother had tears in her eyes that night. Monique would not see her for a long time.

The next day, Monique set off early with her uncle, aunt and grandmother on a three-day journey. Travelling on foot and by boat, with Monique in their arms, they went more than 100 miles from her birth village, Babadi, in the southern central Kasaï province in the Belgian Congo, to her new lodgings, the Catholic mission of the sisters of Saint-Vincent-de Paul in Katende. It was 1953 – the year Joseph Stalin died and Queen Elizabeth II was crowned – and Belgium still ruled the Congo, a vast African territory 75 times its size.

Decades later, Monique remembers herself on the first day at the mission: a tiny girl lost in a crowd, looking everywhere for her family, who had to leave her there. “I cried, I cried, I cried, there was no one.” An older girl gave her a slice of mango and took her in her arms. “From that day it was the end of my life with my family,” she recalls.

Monique Bitu Bingi was one of many mixed-race children forcibly separated from their parents and sequestered in religious institutions by the Belgian state that ruled Congo, Burundi and Rwanda. Her Congolese mother was 15 when she was born; her father was 32, a colonial official from a well-to-do family in Liège. Monique’s existence – and thousands of other mixed-race children known as métis (mixed race) – deeply alarmed the Belgian state, which viewed these babies as a threat to the white supremacist colonial order.

Now more than 70 years after being taken away from her mother, Bitu Bingi, and four other women have accused Belgium of crimes against humanity for their forced removal and placement in religious institutions. Bitu Bingi brings the case with Léa Tavares Mujinga, Noëlle Verbeken, Simone Ngalula and Marie-José Loshi, whom she describes as sisters. All five arrived in the Katende mission between 1948 and 1953, aged three and four; the last left in 1961.

The five women, four of whom live in Belgium and one in France, await a ruling from Belgium’s court of appeal this week, in what is likely to be a charged moment in the country’s reckoning with its colonial past.

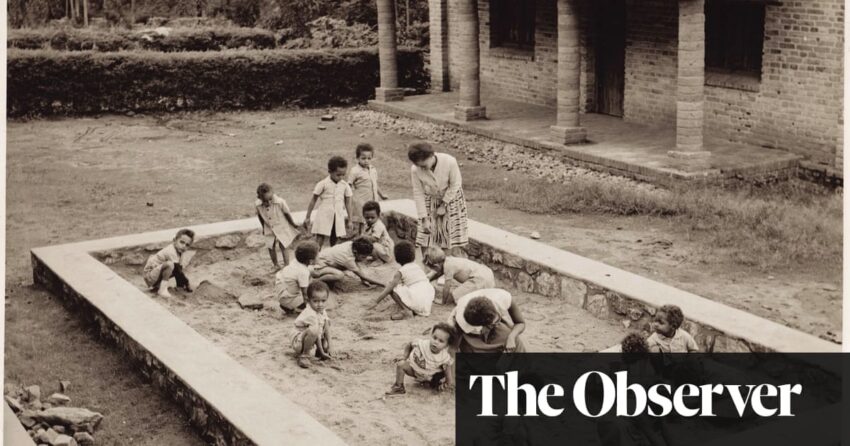

The case has thrown a spotlight on the state-sponsored seizure and segregation of children that is little known. It was a system where breastfeeding toddlers were taken from their mothers; family names and even birth dates were changed; and children were lodged hundreds of miles from their homes, only to be abandoned by the state in the violent chaos of Congo’s independence in 1960.

It was a system underpinned by menace. Bitu Bingi discovered years later that her uncle, the family’s main breadwinner, was threatened with military service at a distant outpost if he did not give her up. Desperate mothers used wax or other substances to blacken their children’s skin to try to hide them.

But the colonial state was determined to find these infants as it grappled with what officials in the late 1940s called “the mulatto problem”, an offensive term to describe mixed-race people. Joseph Pholien, a lawyer who went on to become a Belgian prime minister after the second world war, described Congo’s mixed-race children in 1913 as “an element that could very quickly become dangerous” and imperil the colonial enterprise: “No remedy is radical enough to avoid the creation of métis.”

Arriving at the mission in 1953, Monique’s life was put on a different track. She was told that her father now was “Papa l’état” (“daddy the state”), she said in an interview with the Observer from her home in the east Belgian town of Tongres, near the Dutch border.

This new father was neglectful at best. Monique was hungry nearly all the time. The children’s main meal of the day was fufu (a polenta-like dish), served with vegetables or sweet potato leaves. There was no breakfast. The girls never saw milk, meat or eggs. Monique’s bed in the shared dormitory was against a door that opened into the morgue – the mission was also a hospital.

The girls, shoeless most days, went to school in the village, but knew they were not like the other children. They were “children of sin”, the nuns said. When they fell sick, there was little medicine and less care – the nuns resented their role as state guardians. In dispatches to headquarters, officials complained about the difficulties of finding institutions to house children snatched from their parents.

Life could have continued this way until Monique became an adult. But when she was 11, Belgium’s rule of the Congo came to an abrupt end that no one in Brussels had imagined a few years earlier. After stalling on independence and struggling to contain deadly riots, Belgium bowed to pressure and agreed to cede power. The date was set: on 30 June 1960, the charismatic founder of the first nationwide Congolese political party, Patrice Lumumba, became prime minister of the newly independent nation aged 34. At the handover ceremony, Lumumba denounced the outgoing colonial regime – which had been responsible for the death of millions – for “the humiliating slavery imposed upon us by force”.

The Belgians, represented by King Baudouin, were stunned. Some argued that the African leader signed his own death warrant with the speech, but Lumumba also had enemies at home.

Days after independence, the army mutinied and Lumumba’s government lost control. Rebels in the mineral-rich province of Katanga declared independence, and Lumumba struggled to get international help from a UN riven by cold war rivalries. In January 1961, the young prime minister was assassinated by firing squad in Katanga by Congolese rebels, with Belgian officers present. A Belgian parliamentary inquiry in 2001 found that Belgian government ministers bore “moral responsibility” for events leading to his murder. The Belgian king knew of the plans to kill Lumumba but did nothing to save him, MPs concluded.

As the country fell into chaos, Belgians scrambled to leave. The Katende girls were told they were going to be evacuated to Belgium. Monique and her friends were excited. “We were going to take the plane to go and live with Papa l’état” and “our godmother”, then reigning Queen Fabiola, she recalled. But the nuns flew off without them.

And so began a time of peril for Monique and the other girls, having been entirely abandoned by “Papa l’etat”. Shunted back to Katende, their normal life collapsed. The older children were left to care for babies. There was not enough food, and many of the infants died. Fighting raged outside the walls. Monique recalls UN and Ghanaian soldiers driving up to evacuate the priests and remaining nuns. The children were left behind: “They abandoned us again.”

Then the local militias arrived. The girls became “the toy” of local soldiers. At night, they came for the girls, stripped them naked and raped them. In the day, they brought severed hands of killed enemy fighters into the mission as trophies.

More than 60 years later, the horror of these days is so seared into her memory that a backfiring car or siren blaring in her sleepy local street pitches her back into the deadly chaos of Katende. “There are times when you ask yourself, was this really true? Did I experience this? But it was like this and, yes, I lived through this.”

During these terrifying days, she had no way of tracing her family. Her mother thought she had been rescued with the nuns. Years later, Monique reconnected with her mother, but the bond was never the same: “I loved her very much and I know that she loved me also. But we never had (close) ties, the ties had been broken.”

Monique Bitu-Bingi married in 1966 and lived in the Congo, eventually moving to Belgium in 1981, seeking a better quality of life for her family. Arriving in Tongres, she had no right to Belgian citizenship, which she eventually acquired in 1999 after a long legal battle, despite having been brought up as a ward of the state. “Papa l’état did nothing,” she recalls.

Many of the wards of the former colonial state would struggle to obtain Belgian nationality. One of the women, Loshi, according to her lawyers, filed an application for Belgian citizenship as early as 1994 from Kinshasa, but was told by the Belgian authorities she would never be successful as such applications “didn’t work for the métis”. She eventually settled in France.

Michèle Hirsch, a lawyer, heard Bitu Bingi’s story for the first time in 2018. She and the four other women came to her office on the upmarket Avenue Louise in Brussels. Seated around a glass table on minimalist black chairs, they recounted a childhood of forced removal, hunger, rape and abandonment. Hirsch, who had previously represented victims of the genocide in Rwanda, was not sure at first what to do. The people in charge of the policy had long since died, she thought. But she saw “the courage they had to put this story in our hands” and turned to the archives.

What she found, she told the Observer, was “a systematic policy to identify, track and pursue mixed-race children, taking them from the arms of their mothers and forcing them under the guardianship of the state”. This policy was made possible by two late-19th century decrees from when King Léopold II ran the Congo as his own private fiefdom. After the second world war, it was strengthened by a 1952 law that said children could be removed from their parents “for any reason whatsoever”.

“The legislator in 1952, after the judgments of Nuremberg, after the war, adopted a racial law that allowed children to be placed under the power of the state… uniquely because they were métis,” Hirsch said. She told the court there were “troubling similarities” with the Nazi policy of seizing children of German-Polish parents, which was also condemned at Nuremberg.

The Belgian government argued that while the policy did not reflect modern values, it was not a crime at the time. A lower court agreed. In a judgment in 2021, the Tribunal of First Instance also said: “The fact (these acts) are unacceptable… is not sufficient to also allow them to be qualified, in law, as crimes against humanity.” It ordered the women to pay €6,000 (£5,000) to the state. Under Belgian law, plaintiffs are required to pay a proportion of their opponents’ costs, although the judgement will only be enforced if they lose on appeal.

The Belgian foreign ministry declined to give an interview or to provide information on the state’s arguments, saying: “We never comment on ongoing legal cases.” The law firm Xirius, which represented Belgium at the tribunal, did not respond to requests for an interview. Some legal scholars have offered support to Belgium. The late professor of international law, Eric David, told Belgium’s Le Vif in 2020 that: “The crimes against humanity judged at Nuremberg in 1945-46 had nothing comparable to the forced placement of mixed-race children in religious institutions.”

Hirsch is hopeful the appeal will succeed, saying that her team has brought thousands of unseen documents “out of the dust” of the archives that demonstrate how the policy worked. Lawyers have drawn on the work of Assumani Budagwa, an independent researcher, who came to Belgium as a refugee in 1979 from DR Congo (then known as Zaire), and has spent nearly three decades uncovering the unknown history of these stolen children. “It is a shameful page, it is a painful page, and to bring it into the open is not easy, like all the pages of history concerning violence and atrocities when the colonial propaganda spoke of civilisation,” he said.

Belgium has made hesitant progress in confronting the past. In a landmark resolution in 2018, its parliament recognised that the métis had been victims of “targeted segregation” and “forced removals”. A year later, then prime minister Charles Michel made an official apology, focusing on children removed from their African mothers between 1959-1962 and sent to Belgium. The Belgian state, he said, had “committed acts contrary to the respect of fundamental human rights”.

But a two-year special commission on the colonial past set up by the Belgian parliament after the Black Lives Matter protests has gone nowhere. A 729-page report with dozens of recommendations finalised nearly two years ago has been gathering dust because of political deadlock over the question of an official apology for the entire colonial period.

This week, the five women will hear the decision of the appeal court, housed at the monumental Palais de Justice in Brussels. If they lose their case, they can appeal to Belgium’s highest court of the judiciary, the court of cassation, but only on a point of law. The five women are seeking €50,000 in compensation each. It is a “very small” amount, Hirsch said, because if they lose, they must pay the state compensation, calculated as a proportion of their claim.

Budagwa, the researcher, thinks that the state fears paying reparations if it loses. When Michel made his apology, it was reported that 20,000 children were affected by the policy, but Budagwa believes this is an inflated figure not based on historical evidence. Researchers for Résolution-Métis, an official body, are investigating how many children were removed from their parents, but said sources were “deficient and fragmentary”.

For Monique Bitu Bingi, an apology is too little. “For a human life, saying sorry isn’t enough. I want the state to assume its responsibility, to recognise (what happened) and make reparation. Because we were destroyed, mentally and physically.”