Concussions are a common injury in youth sports that involve contact or collision.1 While there is substantial variability in time to recovery in pediatric populations,2 most youth athletes diagnosed with concussion return to playing sports once symptoms have fully resolved.3 Medical disqualification from sport (ie, where a healthcare provider does not clear an athlete to return-to-play after their symptoms have fully resolved) is uncommon,4,5 but returning to sport is not without risk. Recommendations suggest that decisions about returning to sport after symptoms have resolved should be informed and individualized.4,6,7 However, data about this decision for youth athletes is highly limited. On the one hand there is no definitive longitudinal evidence of a dose–response relationship between concussions sustained in youth sport and later-life neurodegeneration.8 On the other hand, data from a convenience sample of deceased young contact sport athletes,9 retrospective cohort studies of professional athletes,10 and animal models11 suggests that repetitive brain trauma may have lasting consequences. Not surprisingly, many parents are concerned about concussion12 and seek counsel from sports medicine clinicians about their child’s return to sport after injury.13 A report from the Institute of Medicine indicates a need for effective communication strategies to facilitate such discussions involving youth athletes and their parents.14

Shared decision-making (SDM) approaches may help facilitate discussions and decision making about returning to sport after concussion recovery.6 Shared decision-making is considered appropriate when there is more than 1 medically reasonable option.15 Consistent with the Ottawa Decision Support Framework,16 core components of SDM include the patient or patient surrogate having adequate knowledge (that decision needs to be made, what different options are, and about the risks and benefits of different options), values clarity (being clear on what matters most to them in making this decision), and support (having the role they want in decision making, without pressure from others).17 Evidence in other domains finds that SDM leads to greater patient confidence that the decision they made was the right one for them.18 Shared decision-making does not require clinicians to be fully agnostic in how they frame decisions. Opel’s15 pediatric SDM process framework proposes that clinicians may engage in SDM in a more or less directive manner depending on their medical recommendation and the strength of family preferences.

Most conceptual15 and empirical18 research on pediatric SDM centers on the clinician–parent dyad, with parents acting as patient surrogates. However, as children progress through adolescence and approach adulthood, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that they have increased agency in health-related decision making.19 Such engagement is important for ensuring decisions adequately reflect adolescent preferences, and because it may support growth in their efficacy in making healthcare-related decisions.20 We adopt the World Health Organization’s definition of adolescence as encompassing the 10 to 19 years age range21 while recognizing that there is substantial interindividual variability across this age range in the timing of biological and social role changes that may affect decision-making needs and capacity.22 Emerging findings in other domains indicate that some clinicians are modifying how they engage in SDM to meet what they perceive to be developmental needs of adolescent patients.22–24 However, adolescent-relevant best practices for SDM have not been formally articulated nor have strategies for managing potential discordance within the parent-adolescent dyad.25

Using qualitative methods and framed by the Ottawa Decision Support Framework,16 the present study addressed the question of how sports medicine clinicians support decision making about sport participation after concussion recovery with adolescent patients and their parents. Specific areas of inquiry related to how clinicians framed the decision, what factors they considered in how they approached the decision process, and how they navigated discordance within families.

METHODS

Sample and Procedure

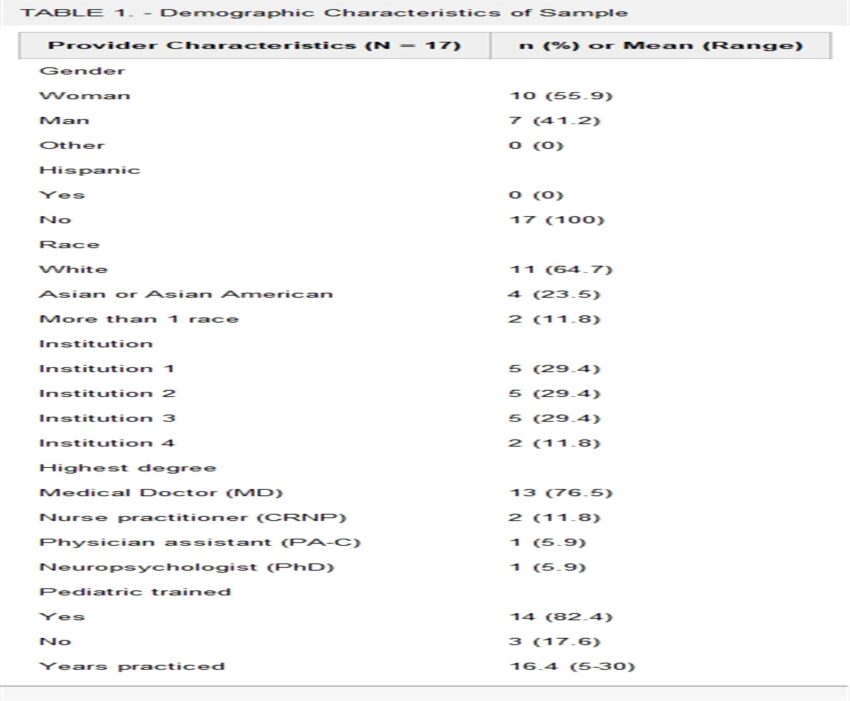

A purposeful sample of 17 clinicians from 4 children’s hospitals (located in the Northwest, Southwest, Midwest, and Northeast regions of the United States) were recruited for individual interviews. Clinicians were eligible if they provided postconcussion care to adolescent patients within a sports medicine group or division. Patients receiving postconcussion care in such settings include those who sustained a concussion while participating in their sport and those who sustained a concussion outside of sport but who are looking to return to their sport after they recover. As detailed in Table 1, most were physicians (MDs) and board certified in Sports Medicine, with the sample also including pediatric neurologists, nurse practitioners, and physicians’ assistants. Most (n =14, 82%) were pediatric trained. The initial sample estimates achieved data sufficiency, and thus, the sample size did not change after an early review of transcripts.26 All interviews were conducted remotely, and participants each received a $30 gift card incentive. Interviews were digitally recorded, professionally transcribed verbatim, and spot checked by interviewers to ensure data integrity. The Seattle Children’s Research Institute Institutional Review Board approved the study procedures and granted a waiver of documentation of consent. Information describing the research was provided to all participants before study activities. This report conforms to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.27

Demographic Characteristics of Sample

| Provider Characteristics (N = 17) | n (%) or Mean (Range) |

| Gender | |

| Woman | 10 (55.9) |

| Man | 7 (41.2) |

| Other | 0 (0) |

| Hispanic | |

| Yes | 0 (0) |

| No | 17 (100) |

| Race | |

| White | 11 (64.7) |

| Asian or Asian American | 4 (23.5) |

| More than 1 race | 2 (11.8) |

| Institution | |

| Institution 1 | 5 (29.4) |

| Institution 2 | 5 (29.4) |

| Institution 3 | 5 (29.4) |

| Institution 4 | 2 (11.8) |

| Highest degree | |

| Medical Doctor (MD) | 13 (76.5) |

| Nurse practitioner (CRNP) | 2 (11.8) |

| Physician assistant (PA-C) | 1 (5.9) |

| Neuropsychologist (PhD) | 1 (5.9) |

| Pediatric trained | |

| Yes | 14 (82.4) |

| No | 3 (17.6) |

| Years practiced | 16.4 (5-30) |

Data Tools

Interview guides were developed according to study goals and adjusted as necessary throughout data collection as per standard qualitative methodology.28 The question guide was structured by the core components of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework,16 addressing how clinicians approached the decision with families. Clinicians were encouraged to describe a recent visit and provide specific examples of their communication with families (see Supplementary Document 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, https://links.lww.com/JSM/A424). We note that such communication and decision making was about returning to sport after the injured athlete’s symptoms resolved. All participants also completed a brief demographic questionnaire.

Analysis

Data were uploaded into Dedoose Version 7.0.23 (Sociocultural Research Consultants, Los Angeles, California) for coding and analysis, following procedures outlined by Braun and Clarke.29 Steps to codebook development were as follows: initial codes were derived from study goals; codes were augmented by a reading of 2 transcripts; codes were tested on 3 additional transcripts by both coders; the codebook was edited until an exhaustive, but manageable, code list was reached. We used a multistep approach to developing the codebook, which allowed for both deductive codes extracted from study goals, instruments, and frameworks, and inductive codes emerging from review of transcripts. Each transcript was open coded by 2 coders blinded to each other’s coding; differences were resolved by discussion until 100% agreement was reached. During synthesis, coded excerpts were systematically summarized into themes and subthemes with associated quotes.

RESULTS

Participant demographics are presented in Table 1. Themes and example quotes are presented in Tables 2–4 and are summarized below with reference to the specific areas of inquiry. Quotes are reported by participant number and site number.

How Did Clinicians Frame the Decision?

| Subtheme | Illustrative quotes |

| Risk | Quote 1a.1: “I try to ease their mind just a little bit just by saying, again, a lot of the research you’re seeing and hearing about that’s scary is in relationship to football athletes that have been banging their heads for decades, so a lot different than my high school soccer athlete even if they’ve had multiple concussions. So, trying to ease them a little bit from that standpoint.” (115; Inst 4) |

| Quote 1a.2: “Letting them know what we know and what we don’t know as far as risks. And the possibility of having worsened symptoms with that further injury or possibly long-term symptoms with further injury, we don’t know that, but it’s a possibility.” (118; Inst 4) | |

| Quote 1a.3: I think we’ve got to be confident in what we’re kind of trying to let them know. If I’m wishy-washy, then that doesn’t help as much.” (115; Inst 4) | |

| Quote 1a,4: “Yeah. I mean, I think the times I bring it up are definitely when we’re getting into the multiple concussions realm. And again, that’s kind of a very vague answer because even multiple—what does that mean? Because I’ve let athletes get back to sport after 3, 4, 5 concussions. And then I’ve kind of also, after 1 or 2, have had the conversation, like I don’t know if you’re ready to get back or whether you should ever play this sport again.” (115; Inst 4) | |

| Quote 1a.5: “And then if you’re somebody who takes months and months to recover each concussion, and you wanna go back to a really high-risk, collision contact sport, we do have a conversation with the families and say, “Our medical advice may be that you don’t go back to this sport.” (108; Inst 2) | |

| Alternative activities | Quote 1b.1: “Realizing that you’re somebody that really wants people to be active. And then you have to limit that—sometimes you have to—hopefully not limit. I guess it’s alter or change the activity. You really worry that you’re upsetting an apple cart.” (101; Inst 1) |

| Quote 1b.2: “We don’t actually have the discussion of we’re going to change your sport. We’re going to say, “This is your third injury playing basketball. Basketball is a pretty low-risk sport anyway. So, how can we—now that you’re better, is there anything we can do now to make it less likely that you’re just going to be back here in 6 months with another injury?” And then you can talk about different things. You can talk about untreated comorbidities, you can talk about other causes of symptoms, you can talk about sometimes changes in practice or play, and sometimes in there you can talk about changing the sport. So, you give them a number of different options and then the family sort of settles out where they feel comfortable.” (111; Inst 3) | |

| Quote 1b.3: “If they’re a multi-sport athlete and had a concussion during one of those higher-risk sports but they play 3 other sports anyway, I think that’s an easy way to kind of bring it up, you know, if you have all these other interests, do you think it might be worthwhile to focus more on sports with a little bit of a lower risk for concussion?” (107; Inst 2) | |

| Quote 1b.4: “I try to ask them, what sports are more important to them, so, we can try to find some kind of alternative. I think somebody who’s athletic and competitive and used to being active they’re not (going) to just want to totally give up sports. And I certainly don’t want them to totally give up sports either, I think, sports are important for a lot of different reasons. It’s seeing if we can find something that may be a safer alternative.” (118; Inst 4) |

What Factors Did Clinicians Consider in How they Approached the Decision Process?

| Subtheme | Illustrative quotes |

| Sport benefits | Quote 2a.1: “Each individual has certain goals in regard to their return to sport. And that can be weighed by the athlete and the family and their long-term goals. Whether that’s at a recreational, exercise level to an elite level.” (105; Inst 1) |

| Quote 2a.2: “The factors that might lead you against changing a sport, which I also have to consider, is a number of years of commitment to a particular sport. It’s usually harder to persuade people. If they have had relatively few injuries in the sport, if they’re getting a lot of benefit from the sport, if they’re a team leader, if they’re going to have a scholarship.” (111; Inst 3) | |

| Athlete identity | Quote 2b.1: “It is that kid that their identity is their sport. The one that’s also looking for the scholarship or thinks that they’re going to play beyond their middle school or high school years. So, then having a discussion that I’m taking away that sport is really difficult… I mean, I think a lot of the patients I tend to see have been in whatever particular sport for a long time, and so they’re not willing to kind of just give it up unless they absolutely have to. That’s what I would say a good percentage of my athletes are.” (115; Inst 4) |

| Quote 2b.2: “Everybody retires at some point in their career with their sport. So, some people, it’s early on. Other people, it’s when they’re older. But at some point, you have to think about when you’re going to retire. So, it’s good to just think about it the entire time that you’re playing to make sure that you have it in the back of your mind.” (108; Inst 2) | |

| Adolescent preferences | Quote 2c.1: “I think a lot of times we assume that’s (returning to the sport where they were injured) what the kid wants to do. And I don’t know that I’m great about always asking about that, but maybe we should.” (107; Inst 2) |

| Quote 2c.2: “Yeah, so, usually I try to make it non-pointed question, because if you ask the child a pointed question in front of their parents, they’ll give you the answer the parent wants to hear, right.” (116; Inst 4) | |

| Quote 2c.3: “So, I find that it really is just asking them because otherwise, I don’t do a very good job of reading their minds.” (110; Inst 2) | |

| Psychological readiness | Quote 2d.1: “If you’re playing scared, you’re gonna hurt something else because you’re just trying to overprotect. And there’s an anxiety component there that we need to address before we can get you back out on the field.” (108; Inst 2) |

| Quote 2d.2: “If they have reservations about playing the sport, we either talk about giving them more time to recover or, do you wanna do something else? A lot of times, if it’s to be honest with you, if they don’t wanna go back to the sport, it sometimes doesn’t have anything to do with the concussion. Has to do (with), they never wanted to play it in the first place.” (102; Inst 1) |

How Did Clinicians Navigate Decision Making Involving Multiple Parties?

| Subtheme | Illustrative Quote |

| Types of discordance | Quote 3a.1: “One parent is gung-ho, one parent is mortified.” (111; Inst 3) |

| Quote 3a.2: “One parent thinks this is silly, the other parent is scared to death.” (113; Inst 4) | |

| Quote 3a.3: “It’s hard because you (parent) only want the best for your kid. You want them to do well. But you also want them to be happy. And they’re (parents) so focused on sports and doing well that I think kids just wanna please their parents. So, it’s an added stressor for the concussed athlete.” (106; Inst 2) | |

| Quote 3a.4: “Mom had preemptively called and said, “I just want the doctor to clear him. Give him what he wants. I don’t want him to know what all this could mean.” (113; Inst 4) | |

| Mediation | Quote 3b.1: “When there is discord, the 2 sides are so anxious or worried or reactive in their opinion that they’re not listening to the other party. They’re just reacting. And so, if I can create a situation where, even if they disagree, if they can hear the other one, that tends to minimize the tension and that creates more of an opportunity to have a discussion about—okay, I hear you, this is why it’s important for you, and this is what’s important about it.” (112; Inst 3) |

| Quote 3b.2: “So, we try to keep our focus on what’s the best information and decision for the child. And sometimes, although not often, sometimes that means pushing back against what the parents want or what one parent wants.” (111; Inst 3) | |

| Quote 3b.3: “I’ve taken parents out of the room and talked to them separately and said, “It’s your reaction to this that is prolonging these problems.” I don’t do that very often. That’s the big sledgehammer, which again, fortunately, the softer touch works 99 percent of the time and it’s very rare that you have to sort of read somebody the riot act.” (111; Inst 3) | |

| Quote 3b.4: “You keep taking steps back until you reach a point where you can all agree, and the backstop on that is we all agree we want the kid to be healthy. Then you move forward from there. Risk reduction, healthy activities, good socialization, leadership, and learning these things. And so, then you can move forward from there. So, that—if I had to say there was a formula that you would then adapt to each individual circumstance, that would be it.” (111; Inst 3) | |

| Quote 3b.5 “you know, it’s really funny, because I will get a lot of well, their health is the most important thing, of course, but why aren’t you letting them play, right? So, you get a lot of this kind of initial like, I’m not a horrible person or a horrible parent, but I still think they should be able to play.” (116; Inst 4) | |

| Facilitation | Quote 3c.1: “I would see myself more as a facilitator as opposed to a decision maker, per se. And if they ask my opinion, I will certainly give it to them. But I do feel like as long as I can moderate and facilitate the decision-making path that they’re taking, and as long as I think they’re taking that in a way that is going in a good direction, not a bad direction, then I’m willing to let them drive that bus, so to speak. But there are some things, obviously, that actually—there are some hard stops. (110; Inst 2) |

| Quote 3c.2: “The parents are allowed to be more conservative than the physician, but I do not let them be more aggressive than me… That’s my medical opinion, right? And that’s based on the patient’s whole history of their injury. I’m not swayed.” (116; Inst 4) | |

| Quote 3c.3: “Oh, I agree with the athlete a lot. And I have to remind the parent that the athlete is my patient. The parent is not my patient. So, I have to advocate for the patient.” (102; Inst 1) | |

| Quote 3c.4: “She had learned a lot about herself, about what she wanted in the next little bit for herself and loved soccer but didn’t wanna do it like that anymore. So, I think that was probably one of my most successful feeling cases where (adolescents) have time and space and can make choices for themselves. And again, if she would have said, I really wanna play soccer. Do you think I can? I think that I would have supported her to do that. (103; Inst1) | |

| Quote 3c.5: “I think ultimately, it’s up to the parents. That’s just kind of my viewpoint on things, that kids are kids and parents are parents. So, if the parents are concerned about it, I think ultimately, it’s their decision. (107; Inst 2) |

How Did Clinicians Frame the Decision?

Risk

Clinicians saw their role as providing data-driven counsel to injured athletes and their parents. They reassured families that adolescent athletes differ from professional football players (Quote 1a.1) and taught families about the likelihood of further injury and the possibility—but not inevitability—of long-term symptoms (Quote 1a.2). Although some clinicians talked about the importance of communicating about the uncertainty of risk information (Quote 1a.2), others talked about the importance of not being too ambiguous or ambivalent (Quote 1a.3). To help communicate about risk, some clinicians shared resources (print and online) deemed trustworthy to balance the volume of what they described as misinformation available from online sources. They also talked about popular media being a frequent source of information for families, resulting in fear about mental health, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, and dementia. Clinicians reported emphasizing not only the risk-related impact to the number of concussions sustained but also how the number interacted with other factors (Quote 1a.4). This included recovery length exceeding 3 to 4 weeks (Quote 1a.5), proximity of multiple concussions, symptoms worsening with sequential concussions.

Alternative Activities

When providers believed that an adolescent should consider not returning to the sport in which they were injured, they framed discussions as making decisions about “alternative activities,” as opposed to sport cessation. Such alternative activity conversations were described as open-ended and collaborative. One reason that providers discussed alternative activities rather than sport cessation was because they wanted to prioritize continued physical activity (Quote 1b.1). Typical alternative activity conversations were described as having the following features: (1) Framing the alternative option as limiting risk or exposure, combined with naming other sports that were lower risk; (2) Including the caveat that a decision need not be permanent (“Take a year off and re-visit.”); (3) Identifying acceptable “middle ground” options allowing activities athletes enjoy while limiting risk; (4) Helping the athlete make a decision (Quotes 1b.2 and 1b.3). To help this conversation, clinicians sometimes gave examples of other athletes who successfully tried a new sport.

What Factors Modified How Providers Approached the Decision Process?

Sport Benefits

Clinicians considered the athlete’s level of sport play because they believed it was relevant for understanding the nature of the athlete’s sport-related goals, such as obtaining a college athletic scholarship. Such potential benefits of sport were described as a consideration in a family’s risk/benefit calculation about returning to sport (Quote 2a.1). Families were described as less receptive to conversations about changing sport if the athlete had played a sport for many years and they were believed to be getting “a lot” of benefits from the sport (such as leadership opportunities, or a college scholarship) (Quote 2a.2). For single-sport adolescents, providers reported greater success discussing reducing exposure (eg, continuing with the same sport, but with fewer practices or fewer months per year played).

Athlete Identity

Clinicians explained that they needed to understand the importance of the sport to the athlete and their motivation for playing sports if they were to best advise the athlete. Clinicians recognized that for some athletes, the sport was their entire identity (“their oxygen”). When sport was central to an adolescent’s identity, they considered the impact that retiring from sport could have on the athlete psychologically. Conversations about retiring or changing sport were seen as more challenging when sport played a central role in the adolescent’s identity (Quote 2b.1); for this reason, younger age and multisport athletes also tended to be more open to considering alternative activities/sports. Specific techniques to manage these discussions included: acknowledging sport to be part of the adolescent’s identity that could result in their feeling incomplete without it; aligning themselves with the adolescent to demonstrate cooperative support; discussing other potentially enjoyable activities with the athlete; and emphasizing that fun and exercise are ultimately the most important reasons to play sports and that “everybody retires at some point” (Quote 2b.2).

Adolescent Preferences

Clinicians shared a variety of ways they tried to identify adolescents’ desires regarding return-to-play. Some were so accustomed to players wanting to return that this preference was assumed (Quote 2c.1). For first-time concussions, 1 provider explained they did not ask players their wishes directly for fear of overcomplicating the situation. When clinicians did try to draw out adolescents’ wishes, they were strategic. Indirect questions were often found to be effective: asking adolescents if their sport was fun; how excited they were to return; and what was important to them about the sport. One clinician explained that this approach worked when an adolescent might not answer a direct question with a parent present (Quote 2c.2). In other cases, clinicians found most success by asking directly if an adolescent wanted to return to sport, how they felt about going back, or most often what their goals were for the sport (Quote 2c.3). Some adolescents required no inquiry, instead stating directly that they did not want to play again. Clinicians described paying attention to cues from the adolescent and going “by feel.” This included noticing: adolescent’s presentation (eg, anxious, withdrawn), tension between the athlete and the parent(s), body language, and engagement in conversation with provider. Based on these cues, clinicians sometimes asked parents to leave so adolescent patients could speak more freely. When adolescents expressed reluctance to return to sport, clinicians explored with them why they did not want to play anymore, investigating whether the decision derived from fear or the best alignment with adolescent goals and preferences.

Psychological Readiness

Clinicians reported attending to cues from the adolescent, such as them seeming less excited or not pushing to return, being slow to exercise or engage in sport-related activities like drills, or expressing fear about returning. Moreover, clinicians noted it was important to pay attention to “when things don’t add up” (eg player is back to school, going through return-to-play progression, but still “moody”). Clinicians described their methods for discussing psychological readiness. They addressed concerns players had about returning. They also emphasized the importance of psychological readiness for injury prevention (eg, one who was less ready could be at higher risk for injury because of premature return to play) (Quotes 2d.1). Clinicians described to the athlete what it would look like to play with less confidence (eg, are you moving differently, are you dodging things you would not normally dodge). This sometimes led to more conversation about the player’s real desire to go back to sport (Quote 2d.2). In considering an athlete’s psychological symptoms and their readiness to return to sport, providers considered whether the concussion caused the psychological symptoms, the absence of sport caused them, or whether the etiology was independent of concussion or sport absence. Clinicians reported that discussing the psychological component of returning to play presented the opportunity to encourage the use of psychotherapy services (eg, clinicially-licensed sport psychologist).

How did Providers Navigate Discordance Within Families?

Types of Discordance

Clinicians described different ways they observed discord within families. In some cases, they described explicit, verbalized differences, including cases where athletes wanted to return to sport, but parents were opposed. Explicit discordance was also observed between parents (Quotes 3a.1, 3a.2). This disagreement was described as related to marital conflict (parents separating or divorced and using the child as a tool in their conflict); different prioritization of long-term brain health versus sports success leading to a potential college scholarship; and different perspectives on the seriousness of concussions. In other cases, discordance was unspoken and assumed between parents and adolescents. Clinicians described some athletes as wanting to please their parents rather than honor their own preferences (Quote 3a.3) or parents pushing for the athlete to return to play without explicitly involving the athlete in the decision (Quote 3a.4). In these situations, providers observed, parents might be motivated by ambitions related to their child’s sport achievement.

Mediation

Clinicians reported using mediation strategies to navigate discordance within families: clarifying reasons for differences, providing information, and aligning on athlete wellbeing. Clinicians asked questions to understand the basis and degree of differences between parties—whether between adolescents and their parents, or between parents. When multiple parties were present, clinicians used interviewing techniques: cross-checking, restating, and summarizing to allow each party to really hear each other (Quote 3b.1). Clinicians sometimes talked to each party separately to better understand their preferences and information needs. Clinicians highlighted the importance of being honest and transparent with parents about the medical situation and focusing on giving the best information to make the best decision for the child (Quote 3b.2) rather than serving as tiebreaker between the parents. In some cases, this meant communicating directly to parents about how they were negatively affecting the decision process (Quote 3b.3). Clinicians described a process of “stepping back” repeatedly until they were able to find values or priorities that were shared between all parties; (Quote 3b.4) such alignment between parties was typically athlete well-being. However, parents themselves sometimes expressed conflicting preferences, with wellbeing-related preferences at odds with preferences related to continued play (Quote 3b.5). Families were described as needing time to process information, and clinicians talked about encouraging family discussion outside of clinic before the next follow-up appointment.

Decision Facilitation

Clinicians described themselves as “decision facilitators” (as opposed to more directive “decision makers”), if families were going “in a good direction” (Quote 3c.1). Multiple clinicians described making appraisals about family preferences relative to their medical opinion, and supporting family autonomy when the family’s preferred course of action aligned with their medical opinion or was more conservative (ie, reducing exposure to activities with concussion risk) (Quote 3c.2). Although clinicians saw themselves as “advocates” for the adolescent athlete (Quote 3c.3), helping them reflect on their own preferences, and elevating their voices (Quote 3c.4), parents were often viewed as having final decision-making authority (Quote 3c.5).

DISCUSSION

Sports medicine clinicians used elements of SDM after concussion, helping families learn about concussion risk, consider alternatives to returning to the same sport, and align behind shared values of child wellbeing. Consistent with Opel’s pediatric SDM framework,15 they were more or less directive depending on the strength of their medical opinion and the nature of family preferences. Recent scholarship suggests that when there is medical equipoise and uncertain evidence about harms, there may be an ethical imperative to adopt a precautionary framework about decision making regarding sport retirement for pediatric patients.30,31 Clinicians in the present study described what they believed as the lack of definitive evidence about long-term concussion-related harms in pediatric patients, and they did not universally adopt a precautionary approach of discouraging participation in sports with a high risk of concussion. Rather, clinicians used a less directive approach when they either saw no meaningful medical difference between options or when families preferred what they saw as the more conservative option. When clinicians believed there was a medical benefit to modifying the adolescent’s sport participation practices (despite no contraindications that would lead to automatic medical disqualification), or when they did not believe the athlete was psychologically ready to return to the sport where they were injured, they initiated conversations about alternative activities rather than sport retirement. Other persuasive strategies included encouraging short-term and reversible decisions (eg, taking a season off), and telling stories about athletes who successfully switched sports.

In this context, athletic identity was described as potentially limiting adolescent willingness to consider alternative activities. Identity formation is a key developmental task of adolescents, and affiliating with groups or roles is an important strategy for developing a sense of self.32,33 However, identity foreclosure can be a problem among adolescent sport participants, where external pressures and lack of alternative sources of identity and affiliation can lead to a restricted sense of self.34 Individuals with foreclosed athlete identities may have difficulty imagining themselves without their sport and tend to have difficulty transitioning to new activities at the end of their sport career.34 Helping individuals reflect on what matters most to them is a key element of SDM.16 For individuals with a narrow or foreclosed athlete identity, enhanced approaches to such values clarification may be needed.35 For example, psychotherapeutic strategies such mindfulness and acceptance36 may be helpful in generating the psychological flexibility necessary to imagine a self without sport achievement.35 Whether or not an athlete chooses an alternative activity after concussion recovery, making this decision with a less restricted sense of self should theoretically lead to less decisional regret.35

Navigating within-family discordance was an important area of focus for clinicians. Although between-parent discordance was described as overt, adolescent–parent discordance was sometimes more difficult to ascertain and required exploring adolescent preferences subtly or without parents present. Previously, negotiation skills have been described as important for navigating multiple competing preferences in pediatric SDM while not “alienating” any party.37 Extending this literature, many clinicians in this study saw themselves as “facilitators” and used active mediation approaches to help families with discordant preferences make a decision. This included clarifying the basis and degree of differences between parties, addressing information gaps that might be driving these differences, and working to align all parties behind a shared value of adolescent well-being. Notably, adolescent well-being was not just a function of the risk of concussion-related harms but included subjective and adolescent-centered dimensions of psychological readiness, sport enjoyment, and other goals and priorities.

LIMITATIONS

This study only considered clinician perspectives. Responses may have been subject to social desirability bias or may reflect aspirational rather than normative practices. Triangulating responses with data from adolescents and families would provide a more complete picture of communication process. Participants in this study were largely board-certified sports medicine clinicians, working in tertiary care pediatric sports medicine clinics led by individuals who are highly invested in, and knowledgeable about, pediatric concussion. We anticipated that clinicians practicing in tertiary sports medicine settings would be exemplars of concussion communication done well rather than typical care in a nonspecialist setting. Individuals receiving care from a specialist tend to either have been referred from a primary care clinician because of complex or lasting concussion symptoms, or self-referred by highly health literate parents.38 Strategies used by clinicians in this study provide an important foundation for how clinicians in other settings can support families postconcussion. Other factors, such as racial and ethnic concordance between family and provider, acculturation, and language ability may have also affected family–provider communication and should be explored in future studies. We note that our investigation focused narrowly on conversations about returning to sport. The nature of family–provider communication about activities after concussion is more expansive, including topics such as returning to school. We also note that interviews focused on adolescents broadly. There are developmentally important differences between early and late adolescents that may affect how they engage in decision making postconcussion, and these require more nuanced interrogation in future studies.

IMPLICATIONS/RECOMMENDATION

Sports medicine clinicians engaged in SDM with parents and adolescents about sport participation postconcussion. Results fit within Opel’s pediatric SDM framework, extending its application to include adolescents as part of the decision-making process. Strengths and strategies shared by clinicians in the present study provide a foundation for future intervention development work to support informed and value-consistent decision making about sport participation after concussion within families. Such support may be of heightened utility for nonspecialist clinicians who are less familiar with this issue than the specialist clinicians who participated in the present study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the sports medicine clinicians who participated in interviews for this study.

References