INTRODUCTION

Sports-related concussion (SRC) is a common area of research in sports medicine. The distinction between SRC, non-SRC, and traumatic brain injury was driven by sporting bodies to establish clear guidelines for recovery and return-to-play for athletes.1 The incidence of SRC in the United States is not known because of a lack of mandatory reporting, though a commonly cited number for traumatic brain injuries is 2.8 million, based on the 2013 emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths in the United States.2 The incidence of SRC varies by level of play (eg, high school vs college), sex, and sport.3

Numerous studies have examined SRC knowledge and reporting behaviors in student-athletes (S-As) at various levels of play.4–8 Register-Mihalik et al4 studied these variables in high school athletes and found that improved SRC knowledge and a more favorable attitude toward reporting were positively correlated with higher reporting behaviors. McAllister-Deitrick et al8 looked at SRC knowledge and reporting behaviors among collegiate athletes and found that female athletes had higher SRC knowledge than male athletes, while male athletes were less likely to report suspected concussions. Another study examining factors associated with concussion nondisclosure in collegiate S-As found that certain variables, including male sex, high concussion-risk sport participation, and increased concussion knowledge, were each associated with concussion nondisclosure.5 Similar findings have been reported in other studies.7,9 SRC knowledge in coaches has also been evaluated.10 To our knowledge, no study has explored SRC knowledge in athletic trainers (ATs) in relation to S-As.

The State of Hawai’i legislature passed laws to establish a concussion educational program for those younger than 19 years.11 The laws also require annual concussion awareness training for coaches, administrators, faculty, staff, and sports officials. Notably, college-aged students and those involved in the care of these students are not included in this legislation. At the collegiate level, the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) requires compliance with their Concussion Safety Protocol, which is a checklist that ultimately serves as a general guide.12 Schools are also required to comply with the “Interassociation Recommendations: Preventing Catastrophic Injury and Death in Collegiate Athletes”, which contains content specific to SRC management endorsed in 2019 by the NCAA Board of Governors. However, the content of SRC education is not mandated to be standardized across member institutions.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate SRC knowledge levels in S-As and ATs, SRC reporting behaviors in S-As, and differences in SRC knowledge and reporting behaviors in S-As based on sex, year-in-college, and sport-type, and history of SRC.

METHODS

Participants

This was a cross-sectional, retrospective survey study of NCAA Division 1 S-As and ATs (staff and graduate assistants) at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. Participants were excluded if they were younger than 18 years or currently experiencing or being treated for an SRC.

Survey

The survey was created based on modifications of 2 prior validated surveys by Register-Mihalik et al and Beidler et al with Cronbach’s α of 0.72 and 0.65, respectively, and including questions on respondent demographics, SRC knowledge, SRC history, and SRC symptom reporting behavior.4,13 Three additional questions on SRC signs and symptoms were added to be consistent with current SRC assessment guidelines.14 The survey was reviewed by a board-certified academic sports medicine physician with extensive experience in SRC management, and a biostatistician. One point was awarded for selecting a correct SRC symptom and for not selecting an incorrect distractor symptom. A higher score represented greater SRC symptom knowledge. Both S-As and ATs completed the SRC knowledge portion of the survey. S-As additionally answered questions on their history of formally diagnosed or self-identified SRC and whether or not they had reported these to a medical/authority figure (eg, physician, AT, coach, or parent). A definition of SRC was provided in the survey for the participants only after they completed the SRC knowledge section. Those who stated that they did not report a prior SRC were asked to identify from a list of reasons why they did not. The survey instrument is included in Supplemental Digital Content 1 (Supplemental Appendix 1, https://links.lww.com/JSM/A480).

Surveys were administered during preparticipation physicals and athletic training room medical visits between July 2023 and September 2023. Respondents had the option of completing the survey using paper-and-pencil or electronically through a QR code link. All participants provided written informed consent and could terminate the survey at any time without penalty. Hard copy survey responses were entered into the Google Form online survey platform and subsequently downloaded as a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation 2021, Redmond, WA) sheet for statistical analysis. Average survey completion time was less than 10 minutes.

Statistical Analysis

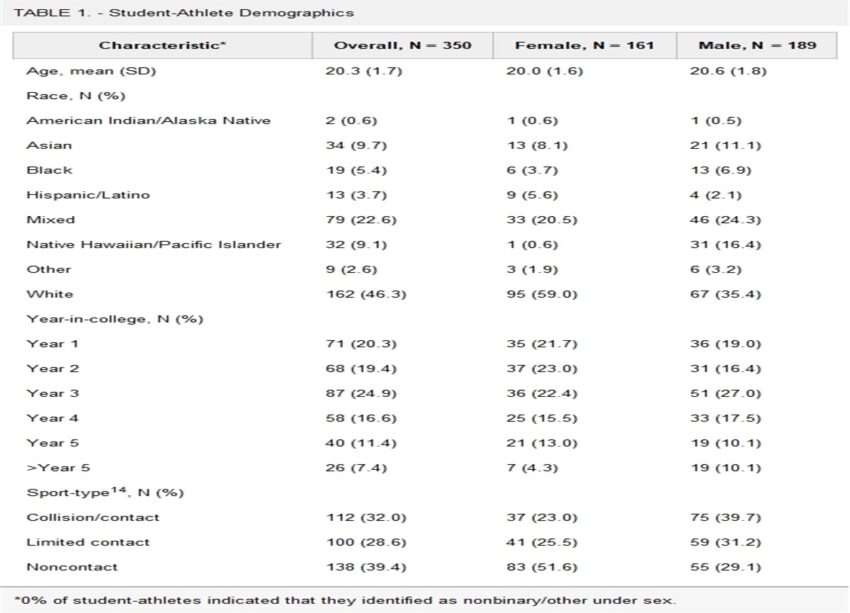

Demographic variables were summarized by frequencies and percentages for categorical variables (eg, race, sport-type), and means and standard deviations for numerical variables (eg, age). The demographic characteristics of the S-As were compared across sexes using appropriate statistical methods. We used the χ2 test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for numerical variables. Sports-related concussion scores were reported as medians with interquartile ranges and were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum or Kruskal–Wallis tests across different groups, including sex, year-in-college, and sport-type, and between S-As and ATs.

Individual sports were grouped by sport-type into 1 of 3 categories: collision/contact (C/C), limited contact (LC), and noncontact (NC).15 C/C sports were football, cheerleading, soccer, water polo, and basketball. Limited contact sports were baseball, volleyball, beach volleyball, and softball. NC sports were golf, swimming and diving, tennis, sailing, cross country, and track and field.

Among the subset of athletes who experienced SRC, reported cases were summarized in terms of percentages and counts. The association of SRC reporting with sex, year-in-college, and sport-type was examined using the χ2 test or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate. All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (v4.3.0, 2023), and a P-value

Ethical Considerations

This original research was approved as exempt by the University of Hawai’i Human Studies Program on July 19, 2023.

RESULTS

Demographics

The survey response rates were 67.3% (350/520) for S-As and 100% (11/11) for ATs. S-As participated in 21 different sports (mean age 20.3 years, range 18–24; 54% male, 46% female, 0% nonbinary/other). Most S-As self-described as White (46.3%), followed by mixed race (22.6%), Asian (9.7%), and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (NHPI) (9.1%) (Table 1). Athletic trainers had an average age of 33.1 years (range 23–49), 63.6% were women, and self-identified ethnicity was Asian (45.5%), mixed race (18.2%), White (18.2%), Hispanic/Latino (9.1%), and NHPI (9.1%).

Student-Athlete Demographics

| Characteristic* | Overall, N = 350 | Female, N = 161 | Male, N = 189 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 20.3 (1.7) | 20.0 (1.6) | 20.6 (1.8) |

| Race, N (%) | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) |

| Asian | 34 (9.7) | 13 (8.1) | 21 (11.1) |

| Black | 19 (5.4) | 6 (3.7) | 13 (6.9) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 13 (3.7) | 9 (5.6) | 4 (2.1) |

| Mixed | 79 (22.6) | 33 (20.5) | 46 (24.3) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 32 (9.1) | 1 (0.6) | 31 (16.4) |

| Other | 9 (2.6) | 3 (1.9) | 6 (3.2) |

| White | 162 (46.3) | 95 (59.0) | 67 (35.4) |

| Year-in-college, N (%) | |||

| Year 1 | 71 (20.3) | 35 (21.7) | 36 (19.0) |

| Year 2 | 68 (19.4) | 37 (23.0) | 31 (16.4) |

| Year 3 | 87 (24.9) | 36 (22.4) | 51 (27.0) |

| Year 4 | 58 (16.6) | 25 (15.5) | 33 (17.5) |

| Year 5 | 40 (11.4) | 21 (13.0) | 19 (10.1) |

| >Year 5 | 26 (7.4) | 7 (4.3) | 19 (10.1) |

| Sport-type14, N (%) | |||

| Collision/contact | 112 (32.0) | 37 (23.0) | 75 (39.7) |

| Limited contact | 100 (28.6) | 41 (25.5) | 59 (31.2) |

| Noncontact | 138 (39.4) | 83 (51.6) | 55 (29.1) |

*0% of student-athletes indicated that they identified as nonbinary/other under sex.

Sports-Related Concussion Knowledge Scores

Table 2 summarizes SRC knowledge scores in S-As by sex, year-in-college, and sport-type. Female S-As had higher SRC knowledge scores than males S-As (P = 0.01). Sports-related concussion knowledge scores did not differ significantly between the 5 year-in-college subgroups (P = 0.16). The overall comparison among all 3 sport-type subgroups revealed a nearly significant difference in SRC knowledge scores (P = 0.06). Further investigation into pairwise differences among sport-type suggested a significant difference between C/C and NC sports, with respective median scores of 0.788 and 0.727 (P = 0.02).

Sports-Related Concussion Knowledge Scores Among Student-Athletes

| Categories | SRC, Median (Interquartile Range) |

P |

| Sex | 0.011 | |

| Male (N = 189) | 0.727 (0.545, 0.848) | |

| Female (N = 161) | 0.788 (0.545, 0.879) | |

| Year-in-college | 0.156 | |

| 1 (N = 71) | 0.758 (0.545, 0.848) | |

| 2 (N = 68) | 0.727 (0.545, 0.879) | |

| 3 (N = 87) | 0.727 (0.545, 0.848) | |

| 4 (N = 58) | 0.727 (0.545, 0.841) | |

| 5 (N = 40) | 0.848 (0.720, 0.909) | |

| >5 (N = 26) | 0.742 (0.545, 0.848) | |

| Sport-type | 0.058* | |

| Collision/contact (C/C) (N = 112) | 0.788 (0.667, 0.856) | C/C vs. LC: 0.126† |

| Limited contact (LC) (N = 100) | 0.712 (0.545, 0.848) | C/C vs. NC: 0.019† |

| Noncontact (NC) (N = 138) | 0.727 (0.545, 0.833) | LC vs. NC: 0.515† |

*This P-value is for the comparison across all 3 sport-type groups.

†The following 3 P-values are for pairwise comparisons between each sport-type.

Average SRC knowledge scores of the ATs were significantly higher than that of the surveyed S-As, with median scores of 0.970 (IQR 0.894, 0.985) and 0.758 (IQR 0.545, 0.848), respectively (P

Sports-Related Concussion Symptom Reporting to Medical/Authority Figures by Student-Athletes

Overall, 29.1% (n = 102/350) of S-As had experienced a formally or self-diagnosed SRC. Of those, 32% (32/100) responded that they did not report the injury to a medical/authority figure. Tables 3 summarizes S-A SRC symptom reporting behaviors. Male S-As were less likely to report SRC symptoms than female S-As (56.9% vs 83.3%, P = 0.01). There was a statistically significant trend in SRC reporting across year-in-college, as determined by the Cochran–Armitage Test, such that higher year-in-college was associated with a lower likelihood of SRC reporting behavior (P = 0.03). Among sport-type, there was a higher percentage SRC reporting behavior in LC sport than in C/C sport S-As (78.6% vs 51.1%, P = 0.04) and between NC sport and C/C sport S-As (85.2% vs 51.5%, P = 0.008). Sports-related concussion reporting rates did not differ significantly between LC and NC sport S-As. The SRC knowledge scores of S-As who chose to report their SRC (median score 0.788; IQR 0.621, 0.879) compared with those who did not report their SRC (0.803; 0.689, 0.848) did not differ significantly (P = 0.86). S-As who experienced but did not report an SRC were given the opportunity to provide their reasons for not reporting. The most commonly cited reasons were“I did not think it was serious enough;”“I did not want to lose playing time/leave the current game/practice;”and “I did not want to be withheld from future games/practices.”Table 4 provides a summary of reasons given for not reporting SRC.

Number of Student-Athletes Who Chose to Report Sports-Related Concussion to a Medical/Authority Figure

| Categories | Reported SRC to an Authority figure, N (%) |

P |

| Sex | 0.010 | |

| Male (N = 58) | 33 (56.9) | |

| Female (N = 42) | 35 (83.3) | |

| Year-in-college | 0.013 | |

| 1 (N = 13) | 12 (92.3) | |

| 2 (N = 17) | 11 (64.7) | |

| 3 (N = 25) | 16 (64) | |

| 4 (N = 22) | 19 (86.4) | |

| 5 (N = 11) | 4 (36.4) | |

| >5 (N = 12) | 6 (50) | |

| Sport-type | 0.004* | |

| Collision/contact (C/C) (N = 45) | 23 (51.1) | C/C vs. LC: 0.036† |

| Limited contact (N = 28) | 22 (78.6) | C/C vs. NC: 0.008† |

| Noncontact (N = 27) | 23 (85.2) | LC vs. NC: 0.775† |

*This P-value is for the comparison across all 3 sport-type groups.

†The following 3 P-values are for pairwise comparisons between each sport-type.

Reasons for Not Reporting Sports-Related Concussion to a Medical/Authority Figure

| Reason for Not Reporting SRC to an Authority Figure | Number (N = 29) |

| I did not think it was serious enough | 19 |

| I did not want to lose playing time/leave the current game/practice | 14 |

| I did not want to be withheld from future games/practices | 13 |

| I did not know it was a concussion at the time | 11 |

| I did not want to let the team down | 10 |

| I did not want to have to go to the doctor | 6 |

| I felt pressured (from teammates, coaches, parents, and/or fans) to continue playing or thought they would get mad | 5 |

| I was trying to get a scholarship to play in college | 4 |

| I did not have health insurance and could not go to the doctor | 1 |

DISCUSSION

The aims of this study were to evaluate SRC knowledge levels in US collegiate S-As and ATs and to assess SRC reporting habits and reasons for not reporting in S-As.

Among S-As, SRC knowledge levels varied by sex and sport-type, with females and C/C sport S-As demonstrating the highest SRC knowledge scores. Prior studies have shown conflicting results when comparing SRC knowledge levels between males and females at the high school and collegiate level.13,16–20 In gender-comparable sports, the incidence rate of concussion in females is higher than in males.21,22 There may be other factors contributing to differences in SRC knowledge between sex, such as individualized learning style and gendered expectations, which are beyond the scope of this article. Higher SRC knowledge in collegiate C/C sport S-As has been noted by Tashima et al.23 C/C sport S-As are known to be at higher risk of SRC and have a higher incidence of SRC, and, therefore, may have more opportunities to receive SRC education.21,22,24

Interestingly, SRC knowledge scores did not differ significantly by year-in-college. One would assume that with higher year-in-college, S-As would have received more cumulative SRC education. It is also possible that SRC education received may have varied substantially between domestic and international, and transfer S-As before matriculating at this university.

Overall, SRC knowledge scores varied widely among S-As, pointing to deficiencies in the current method of providing SRC education, which includes the NCAA’s “Concussion: A Fact Sheet for Student Athletes.”25 A number of studies have examined various SRC concussion education methodologies and their outcomes. Cusimano et al26 found that in minor league hockey players, SRC knowledge increased immediately after watching an educational video but was not retained at 2-month follow-up. Oral presentations, online modules, and videos, and printed materials are common formats to provide SRC education.27,28 Nonetheless, a qualitative review by Mrazik et al28 found that SRC educational interventions may lead to improved knowledge in the short term but do not translate to long-term knowledge, behavioral, or attitude changes. The importance of knowledge transfer and exchange has been recognized as an important component of SRC education. This requires not only the educational media but also an interactive process, multidirectional and ongoing communications, and consideration of the individual user and context.29 Printed materials seem to have limited efficacy when used alone.29 Instead, SRC education can be enhanced with support groups facilitating peer-to-peer discussion to reinforce knowledge and promote a culture of safety.29

As expected, SRC knowledge scores in ATs were significantly higher than those of S-As. Prior studies have noted higher SRC knowledge scores in ATs than in coaches.30,31 Interestingly, Wallace et al19 found that high school S-As with access to an AT had higher SRC knowledge than S-As without an AT, though this did not result in better SRC reporting rates. Although continuing SRC education of stakeholders such as physicians, ATs, and coaches is justified, the higher SRC knowledge does not always equate to improved S-As safety. For S-As, there is not only a basic knowledge gap but also an SRC culture that needs to continue to shift.

Regarding SRC reporting in S-As, most of those who reported a history of SRC reported it to a medical/authority figure. Similar to prior studies done in collegiate S-As, males and C/C sport S-As were less likely to report SRC than females or LC/NC sport S-As, respectively.5,7–9 Conformity to traditional “masculine norms” of risk taking, winning, and self-reliance and their relationship to SRC reporting has been explored, where higher conformity was associated with decreased SRC reporting intention in both males and females.32

The trend toward not reporting SRC across year-in-college could perhaps be explained by S-As learning throughout their athletic career that being diagnosed with a SRC means loss of playing time while they are recovering. This might lead to development of a more negative attitude toward SRC reporting with time.

Interestingly, S-As who reported SRC did not differ in SRC knowledge scores compared with those who did not report SRC, suggesting that there were other factors besides lack of knowledge that would explain SRC nonreporting, including not wanting to lose playing time and internal pressure to not let the team down. Prior studies have had mixed results regarding the association between SRC knowledge and reporting behaviors, with some showing increased SRC reporting with better SRC knowledge while others have not.4,5,8,17 The top reasons for not reporting SRC were not thinking the concussion was serious enough and not wanting to be withheld from games/practices, consistent with prior studies.4,7,13,33 The various reasons for not reporting SRC, and the relative weight they carry, may also differ depending on sport-type, team versus individual sports, player position, starter versus bench player, practice versus game, and individual personality characteristics. In addition, the decision to report an SRC can also be affected by emotional or reactive decision making at the time of the event. Though relatively few S-As in our study cited pressure from teammates, coaches, parents, or fans as a reason for not reporting SRC, there is still work to be done to create a culture of safety for S-As and improved education for all those who interact with S-As.

Clearly, there are many factors influencing SRC reporting. The NCAA and Department of Defense issued a consensus statement on improving concussion education.34 Cicero et al35 suggested a basic framework of behavior analysis to understand SRC reporting behaviors, stating that educational interventions, attitudes on reporting, and socioecological models where an individual and their interactions with micro-, meso-, exo-, and macrosystems, when evaluated together, have not necessarily improved SRC reporting. Instead, Cicero uses behavior analytic theory—namely, operant behavior, reinforcement, punishment, and extinction—as a guide for interventions. For example, the negative punishment of removal from play after reporting SRC symptoms can be mitigated by actions such as verbally praising the S-A in front of teammates for reporting and refraining from requests to have the S-A continue to play through the game. This may represent a culture shift for some, though fortunately at our institution, most S-As reported their SRC to a medical/authority figure.

This study has several limitations. Given the design of the study, we relied on participants to recall their own history of medical provider-diagnosed or self-diagnosed concussions, introducing both recall bias and lack of confirmation of prior SRC diagnoses. Furthermore, we acknowledge that the questions used to assess SRC knowledge were limited and may overly simplify a complex topic, though given that most participants, aside from ATs, likely did not have extensive medical training in SRC, the level of complexity is likely suitable to the intended audience. To improve specificity and limit confusion, future surveys could incorporate wording to clarify timing of symptoms in relation to the SRC, whether symptoms are a direct or indirect result of SRC, or a free response section as well. For example, those who experience SRC may develop panic attacks that can manifest as chest pain and difficulty breathing, which technically are not direct signs and symptoms of SRC.

In addition, not all sports were represented equally, thus sports had to be grouped together by sport-type, based on contact level characteristics, to have sufficient numbers for analysis. Diving, which is considered a contact sport, could not be differentiated from swimming, an NC sport, because “swimming and diving” were grouped together in the original survey. Similarly, track and field was classified as an NC sport, and individual events were not differentiated in the original survey.

History of exposure to SRC curriculum was also not assessed. This information could have provided additional insight, for example, if there was a discrepancy with reported prior exposure to SRC curriculum and SRC knowledge scores.

Finally, the sample size for ATs was small and the overall study population was limited to 1 NCAA Division 1 school.

CONCLUSIONS

Collegiate S-As displayed highly variable levels of SRC knowledge, with females and C/C sport S-As scoring better. Athletic trainers had significantly higher SRC knowledge levels than S-As. Sports-related concussion reporting also differed based on sex, year-in-school, and sport-type, such that males, higher year-in-school, and C/C sports S-As were less likely to report SRC to a medical/authority figure. Although S-As who did not report SRC had similar knowledge scores compared with S-As who did report SRC, a gap in SRC knowledge and other internal and external motivating factors influence SRC reporting behaviors. This highlights the importance of continued efforts for improving SRC education, knowledge retention and transfer, and creating a culture of safety and positive attitudes toward SRC reporting.

References