INTRODUCTION

Sport-related concussion (SRC) is prevalent1 and can significantly affect adolescent quality of life.2 It increases the risk of subsequent brain and musculoskeletal (MSK) injury. A systematic review and meta-analysis3 found that the risk of sustaining a concussion was more than 3 times greater in children with a prior concussion versus those without a prior concussion (relative risk = 3.64 (95% confidence interval (CI), 2.68–4.96)). Another systematic review and meta-analysis4 found that athletes post-SRC had a significantly greater incidence of MSK injury during the year after return to sport (RTS) when compared with nonconcussed athletes (odds ratio (OR) = 2.11 (1.46–3.06)) and that both male and female participants had a greater risk of MSK injury when compared with their respective same-sex, nonconcussed controls (OR = 2.23 (1.40–3.57) and 2.06 (1.26–3.37), respectively). One study showed that risk for MSK injury is greatest during the first 3 months after SRC (OR = 2.48 (1.04–5.91)),5 whereas others have shown that risk varies across time and/or depends on the type of sport.6,7

Ample evidence indicates that clinical recovery precedes complete physiological recovery from SRC.8 Subtle sensorimotor and neurocognitive deficits identified on balance9 and dual-task10 tests may persist beyond clinical resolution of concussion signs and symptoms, potentially explaining the increased risk of subsequent concussion and MSK injury.11 A cross-sectional study of National Collegiate Athletic Association Division 1 American football and ice hockey athletes12 found that athletes with a concussion within the past 2 years had dynamic balance deficits compared with nonconcussed athletes, suggesting that sensorimotor control deficits may persist beyond clinical recovery. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), Howell et al13 assigned adolescents upon RTS after SRC to usual care or to a Neuromuscular Training Program (NTP). The incidence of MSK injury over the subsequent year in the usual care group was 3.56 times (1.11–11.49) that of the NTP group.

Subsymptom threshold aerobic exercise has emerged as “medicine” to treat SRC.14 Multicenter RCTs confirm that aerobic exercise based on the individual’s level of exercise tolerance on systematic testing prescribed 2 to 10 days after SRC safely facilitates recovery in adolescents15 and significantly reduces the incidence of Persisting Post-Concussive Symptoms beyond 1 month.16 Adolescents who complete aerobic exercise programs return to school and sports faster than patients who stretch or strictly rest.17 However, paradoxically, aerobic exercise treatment may increase the risk of subsequent injury because of greater exposure to rigorous sport activity.

In a recent RCT,16 we randomly assigned adolescents within 10 days of SRC to perform either a targeted heart rate (HR) aerobic exercise program or a placebo-like stretching program. We queried them at 4 months since injury, approximately 3 months after unrestricted RTS, and ensured that our analyses accounted for differences in recovery time. The primary aim of the current analysis was to determine whether individualized aerobic exercise prescribed within 10 days of SRC reduced the incidence of MSK injury or subsequent concussion in athletes who recovered from SRC and had returned to sport. Our secondary aim was to assess differences in return to learn or to sport between the groups at 4 months after injury.

METHODS

This study was a planned secondary analysis of a 1:1 parallel, multicenter RCT that recruited participants from July 2018 to March 202016 and was registered at Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02959216A. A common institutional review board (IRB) was used through SmartIRB, with University at Buffalo and Boston Children’s Hospital relying on Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s IRB. Participants were recruited from outpatient clinics and randomized to perform either aerobic exercise or placebo-like stretching exercise within 10 days of SRC. At 4 months since injury, participants were contacted by email to complete a follow-up questionnaire (see Supplemental Digital Content 1, https://links.lww.com/JSM/A450).

Participants

Sport-related concussion was diagnosed by experienced sports-medicine physicians using recent international guidelines,18 including history, concussion symptoms linked to a head injury, or injury to another part of the body with force transmitted to the head, plus symptom provocation and/or signs on a concussion-relevant physical examination of the autonomic, oculomotor, cervical, and vestibular systems.19,20 Male and female adolescents (13–18 years) presenting within 10 days of injury and diagnosed with SRC were included. Participants were excluded for any of the following reasons: (1) 3-point or less difference between current and preinjury symptoms on the Post-Concussion Symptom Inventory (PCSI);21 (2) more severe injury as indicated by a score

Intervention

The Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test (BCTT)22 was used to assess participants’ level of exercise tolerance at each weekly study visit. Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test determined the HR at symptom exacerbation, called the HR threshold (HRt). The HRt was used to generate individualized prescriptions for participants randomized to aerobic exercise. Participants exercised on the treadmill until voluntary exhaustion or until they reported more-than-mild concussion symptom exacerbation (defined below).

Targeted Heart Rate Aerobic Exercise Prescription

Participants prescribed aerobic exercise were instructed to exercise (ie, walking, jogging, swimming, or stationary cycling) at home or school for at least 20 minutes a day at their target HR, which was 90% of the HRt. Participants were told to stop exercising if they experienced more-than-mild symptom exacerbation, defined as a >2 point increase in concussion symptoms on a 0 to 10 scale when compared with their preexercise value. All participants received an HR monitor (Polar OH1 monitor and Polar Beat app). Participants performed the BCTT weekly and received a new target HR until they recovered or the 4-week intervention period ended.

Placebo Stretching Exercise Prescription

Participants were instructed to perform a standardized combination of light stretches and breathing exercises designed not to elevate HR significantly. They received a Polar OH1 HR monitor to wear while stretching and were instructed to refrain from participation in any other form of physical exercise. Participants performed the BCTT weekly and received a new progressive stretching prescription until they recovered, or the 4-week intervention period ended.

Recovery From Sport-Related Concussion

Criteria for clinical recovery were standardized among the study physicians as (1) resolution of concussion symptoms to preinjury (defined as 2 or fewer new mild symptoms (severity 2/6 or less) on the current compared with the preinjury PCSI); (2) normal physical examination (including resolution of any abnormal oculomotor and vestibular signs); and (3) ability to exercise to at least 80% of age-predicted maximum HR on the BCTT without exacerbation of concussion symptoms. Participants then performed a graduated return-to-play (RTP) protocol.18

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcomes were return to sport (organized or recreational), return to exercise training, return to school, current concussion symptoms, and number of sport-related injuries (MSK or SRC).

Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

A sample size estimation was not performed for this secondary analysis. However, we calculated that 44 participants in each arm would identify a moderate effect size (d = 0.5) at alpha of 0.05 and beta of 0.80. The sample size estimate was not met because the trial ended early because of COVID-19.

Demographics and clinical characteristics were compared at the initial assessment. Duration of recovery was calculated in days as the difference between the date of injury and the date of resolution of symptoms to preinjury baseline, which was subsequently confirmed by a normal physical examination and restoration of exercise tolerance on the BCTT.15,16 Participants who had not recovered by 4 months after injury received a maximum value of 120 days to calculate mean recovery duration. Return to school, sport, exercise training, and incidence of subsequent injury were compared. A Mann–Whitney U test compared continuous measures, whereas a χ2 test compared categorical measures (Fisher exact for cell sizes below 5). Duration of exposure to the risk of subsequent injury after recovery was calculated as the difference in days between the date of medical clearance to begin the RTP protocol and the date of questionnaire completion. A binary logistic regression model predicting the odds ratio of MSK injury using the main effects of intervention (aerobic/stretching), return to sport (yes/no), and days since RTP clearance and 4-month follow-up (days, continuous) was performed. A P value of ≤ 0.050 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS Version 29 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).23

RESULTS

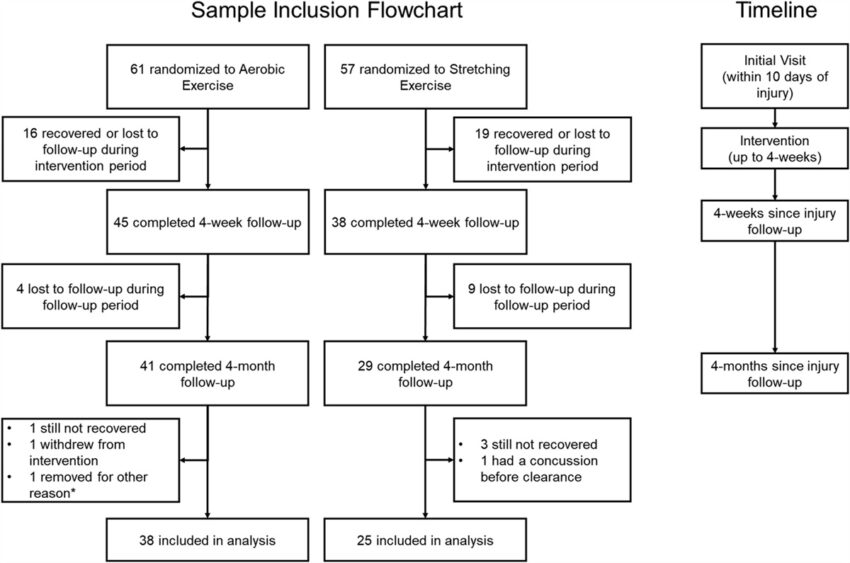

Three hundred eighteen participants were screened from August 1, 2018, to March 31, 2020, and 118 were randomized in the original trial.16 Of the 61 adolescents randomized to aerobic exercise, 41 (67.2%) completed the questionnaire. One participant withdrew from the study, 1 had concomitant neck and shoulder injuries that prevented RTS for 3.5 months, and 1 was still symptomatic from the original SRC at 4 months. Hence, 38 participants from the aerobic exercise group were included. Of the 57 adolescents randomized to do stretching exercise, 29 (50.9%) completed the questionnaire. One participant sustained a concussion (not sport related) before recovering from the original SRC, and 3 were still symptomatic from the original SRC at 4 months. Hence, 25 adolescents from the stretching group were included. There was a higher, albeit marginally nonsignificant, response rate in participants in the aerobic exercise group (67.2% vs 50.9%, P = 0.06). There was no difference in the proportion of participants not recovered by 4 months (2.4% in aerobic vs 10.3% in stretching, P = 0.300 on Fisher exact test). Participants lost to follow-up (n = 48) did not differ from those included in the analysis (n = 63) in age (15.7 ± 1.5 vs 15.6 ± 1.4 years, P = 0.612), sex (61% vs 66% male, P = 0.649), initial PCSI symptom severity (36.9 ± 20.0 vs 35.2 ± 24.1, P = 0.685), or recovery time (23.9 ± 19.9 vs 18.2 ± 14.3 days since injury, P = 0.108). Figure 1 presents the participant inclusion flowchart.

Participant inclusion flowchart. *Reason for exclusion described in text.

Demographics, initial clinical characteristics, and recovery duration are presented in Table 1. Participants in the stretching group were slightly taller and heavier, likely because of the higher proportion of male participants. Adherence to the intervention was 76% for aerobic versus 72% for stretching exercise (discussed in the main trial16). Participants wore HR monitors during home exercise sessions. Those assigned to aerobic exercise significantly raised their HRs, whereas those assigned to stretching did not.16

Demographics, Clinical Characteristics, and Recovery Outcomes

| Aerobic Exercise | Stretching Exercise |

P |

|

| n | 38 | 25 | — |

| Age, yr (SD) | 15.63 (1.49) | 15.87 (1.58) | 0.528 |

| Sex, n (%) male | 22 (58) | 16 (64) | 0.628 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.112 | ||

| White | 31 (81.6) | 20 (80) | |

| Black/African American | 3 (7.9) | 5 (20) | |

| Hispanic Caucasian | 3 (7.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Asian | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Height in cm, mean (SD) | 164.59 (10.08) | 172.50 (8.68) |

0.002 |

| Weight in kg, mean (SD) | 57.72 (12.11) | 68.66 (13.39) |

0.002 |

| Prior concussion, n (%) | 0.528 | ||

| 0 | 20 (53) | 10 (40) | |

| 1 | 9 (24) | 5 (20) | |

| 2 | 8 (21) | 8 (32) | |

| 3 | 1 (2.6) | 2 (8) | |

| Initial PCSI, mean (SD) | 31.95 (21.19) | 39.40 (24.91) | 0.266 |

| Preinjury PCSI, mean (SD) | 2.30 (2.57) | 3.08 (4.34) | 0.658 |

| Abn cervical exam, n (%) | 16 (42.1) | 9 (36) | 0.628 |

| Abn smooth pursuits, n (%) | 25 (65.8) | 12 (48) | 0.161 |

| Abn repetitive saccades, n (%) | 27 (71.1) | 16 (64) | 0.556 |

| Abn horizontal VOR, n (%) | 25 (65.8) | 17 (68) | 0.856 |

| Abn complex tandem gait, n (%) | 13 (36.8) | 11 (44) | 0.570 |

| Days to initial visit, mean (SD) | 5.61 (2.27) | 6.00 (2.48) | 0.469 |

| Days to clinical recovery, mean (SD) | 22.32 (19.45) | 26.92 (22.78) | 0.273 |

Bolded values indicate a significant finding.

PCSI (max score = 132).

Abn, abnormal.

Outcomes are presented in Table 2. The mean time to final follow-up was 129.50 (14.74) and 126.72 (17.88) days for participants in aerobic exercise and stretching exercise groups, respectively (P = 0.308). No differences were seen for any outcomes except that the proportion of individuals who sustained an MSK injury after recovery from SRC was significantly higher for stretching exercise participants.

Three-Month Postrecovery Outcomes

| Aerobic Exercise | Stretching Exercise |

P |

|

| Return to school to preinjury workload, n (%) | |||

| 100 | 35 (92.1) | 25 (100.0) | 0.558 |

| 76–99 | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 51–75 | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 26–50 | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Return to primary sport preinjury participation, n (%) | |||

| 100 | 27 (71.1) | 17 (68.0) | 0.431 |

| 76–99 | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 51–75 | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 26–50 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.0) | ||

| Currently not in season | 8 (21.1) | 7 (28.0) | |

| Current accommodations at school, n (%) | |||

| Full day, no supports | 31 (81.6) | 21 (84.0) | 0.494 |

| Full day, with support | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Out of school for vacation | 5 (13.2) | 4 (16.0) | |

| Return to any exercise or sport preinjury participation level, n (%) | |||

| 100 | 32 (84.2) | 21 (84.0) | 0.321 |

| 76–99 | 3 (7.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 51–75 | 1 (2.6) | 1 (4.0) | |

| 26–50 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.0) | |

| 1 (2.6) | 1 (4.0) | ||

| Did not return | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Follow-up PCSI, mean (SD) | 2.08 (4.83) | 7.75 (22.81) | 0.851 |

| Sport-related MSK injury, n (%) | 2 (5.3) | 6 (24.0) |

0.050* |

| Additional SRC, n (%) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (4.0) | >0.999* |

Bolded values indicate a significant finding.

*P value from Fisher exact test.

Because of different recovery times, the average time from injury to follow-up questionnaire was 3.5 months (107.18 (27.75) days) in the aerobic exercise group versus 3.3 months (99.80 (31.73) days) in the stretching group, which was not statistically different (P = 0.227). We defined a self-report of >75% return to exercise training or to recreational or organized sport as a return to preinjury participation level because this classification would not be affected by the end of the athlete’s primary sport season. Participants in the stretching group had 6.4 greater odds of sustaining an MSK injury when compared with aerobic exercise when controlling for the duration of exposure and return to preinjury sport participation level. The model did not violate assumptions on a Hosmer Lemeshow Test of Goodness-of-fit (P = 0.728). Table 3 presents the results of the binary logistic regression.

Binary Logistic Regression Examining Subsequent MSK Injury

| Variable | β Coefficient | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

P |

| Intervention group (stretching/exercise) | 1.856 | 6.398 (1.135–36.053) |

0.035 |

| Time from date of RTP clearance to date of follow-up | 0.015 | 1.016 (0.984–1.048) | 0.330 |

| Return to at least 75% of preinjury sport participation after recovery | 0.135 | 1.144 (0.101–13.004) | 0.913 |

| Constant | −4.632 | 0.010 |

0.021 |

Bolded values indicate a significant finding.

Individual participant characteristics of the 8 MSK injuries included in the analysis are presented in Table 4. All MSK injuries occurred in male participants, and all had prior concussions.

Individual Participant Characteristics of MSK Injuries

| Injury | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Primary sport | Soccer | Soccer | Football | Soccer | Snowboarding | Football | Ice hockey | Soccer |

| Sport of subsequent injury | Basketball | Soccer | Football | Hockey | Snowboarding | Volleyball | Track | Trampoline |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Male | Male | Male | Male | Male |

| Intervention | Stretching | Stretching | Stretching | Stretching | Aerobic | Stretching | Stretching | Aerobic |

| Age (yr) | 13 | 17 | 17 | 15 | 17 | 15 | 15 | 13 |

| PCSI initial | 21 | 10 | 53 | 56 | 20 | 11 | 12 | 45 |

| Previous concussion | Yes (2) | Yes (2) | Yes (3) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (2) | Yes (2) | Yes (2) |

| Time (d) to recovery from original SRC | 44 | 8 | 15 | 13 | 11 | 13 | 7 | 25 |

| Injury details | Ankle sprain | Ankle sprain | Dislocated shoulder | Wrist injury requiring surgery | Ankle sprain, hand sprain | Dislocated shoulder | Medial tibial stress syndrome | Fractured toe |

| Extremity | Lower | Lower | Upper | Upper | Both | Upper | Lower | Lower |

DISCUSSION

This secondary analysis of a published RCT16 that randomly assigned adolescent athletes within 2 to 10 days of SRC to targeted HR aerobic exercise treatment or to a placebo-like stretching exercise program found that athletes who did stretching exercise had more than 6-fold greater odds of sustaining a sport-related MSK injury in the 3 months after clinical recovery when compared with athletes prescribed aerobic exercise. The initial 3 months after SRC is when the risk of postconcussion MSK injury appears to be the greatest.5 We explored height and weight as potential confounding variables for intervention and MSK injury as they were significantly associated with intervention (Table 1). However, height and weight were not significantly associated with MSK injury and so were not included in the final logistic regression model as confounders. Our final logistic regression model included intervention as a predictor as well as other potential risk factors of MSK injury, specifically, duration of exposure and return to sport. The results remained significant when controlling for time to return to recreational or to organized sport, which accounted for different exposure to the risk of subsequent injury for each group.

The reasons for the lower proportion of subsequent MSK injury with aerobic exercise are unknown. Howell et al24 showed that adolescents within 72 hours of SRC and for up to 2 months had more gait balance control deficits during dual task walking than matched controls. Oculomotor impairment occurs within 1 week of SRC and can persist for weeks to months after injury.25 These physiological data are consistent with the observation that MSK injury risk is greatest within 3 months after clinical recovery from SRC.5 A recent RCT showed that vestibular rehabilitation initiated within the week after SRC improved vestibular symptoms and impairments in adolescent athletes.26 Risk of MSK injury might be mitigated by forms of aerobic exercise (eg, jogging outdoors or indoors on a treadmill, outdoor cycling, swimming) that not only improve cardiorespiratory function but that also involve oculomotor and vestibular input; in effect, functioning as a form of low-grade vestibular and oculomotor habituation/rehabilitation to help prevent the decline in oculomotor and vestibular motor control that accompanies SRC. This theory is supported by the fact that athletes prescribed aerobic exercise in the original trial resolved their vestibular and oculomotor symptoms and physical examination abnormalities upon clinical recovery.16 Why all MSK injuries in this study occurred in male participants is unclear because female participants have been reported to have a greater risk of MSK injury after SRC when compared with female nonconcussed controls.4 This study was not powered to identify sex differences, so the fact that the effect was found in male participants only is likely due to the sample size. Male participants in this sample had a history of having sustained more concussions than female participants, but not statistically significantly more (1.03 ± 0.94 vs 0.64 ± 0.95, P = 0.086). Male participants played more high-risk contact sports than female participants, which may relate to their greater risk of subsequent MSK injury, but further investigation is needed.

Aerobic exercise treatment might also reduce MSK injury risk by mitigating impaired autonomic function that accompanies SRC.27 Adolescents commonly experience orthostatic intolerance (OI) early after SRC, that is, complaints of lightheadedness and dizziness upon standing after supine.28 The vestibular and oculomotor systems interact to regulate blood pressure during position change through the vestibulosympathetic reflex, which defends against OI in humans by increasing sympathetic autonomic outflow29 to maintain homeostasis during movement.30 The vestibulosympathetic reflex is impaired after traumatic brain injury in adolescents,31 and we have shown that OI correlates with an abnormal vestibuloocular reflex on physical examination.28 If aerobic exercise improves or, more likely, blunts autonomic dysfunction after SRC, it may preserve autonomic input into vestibular and oculomotor control during orthostatic and other physical stressors (eg, sport-specific exercise). Improved autonomic regulation of cerebral blood flow during exercise and restored exercise tolerance with aerobic exercise treatment of SRC32 supports this hypothesis. Each male with MSK injury in this study had a history of concussion. We have shown that impaired cardiac autonomic function can persist for years in clinically recovered athletes who report a history of SRC.33 Finally, aerobic exercise reliably increases the neuroplasticity/repair protein brain-derived neurotrophic factor.34 Another potential contributor to the reduction in MSK injury incidence after SRC with aerobic exercise treatment could be BDNF-driven repair of injured oculomotor and vestibular neurons to help restore oculomotor and vestibular function. These hypotheses require further research.

The theory that subtle, persisting alterations in physiological function and neuromuscular motor control underlie a greater risk of MSK injury after clinical recovery from SRC is supported by the efficacy of an exercise rehabilitation program directed explicitly at motor control physiology. In a small RCT, Howell et al13 examined an 8-week NTP (guided strength exercises with landing stabilization focus, 2 times per week) compared with the standard of care in 27 youth athletes after clinical recovery from SRC. The hazard of subsequent injury in the standard-of-care group was 3.56 times (1.11–11.49) that of the Neuromuscular Training Program group over the subsequent year. Factors important for establishing effective interventions to reduce SRC-related MSK injury risk include generalizability and ease of implementation. Although targeted NTPs may be effective, they require direct supervision and instruction by a qualified professional. One of the benefits of individualized, targeted HR aerobic exercise treatment is that supervision is minimal because the exercise is typically done at home or in school.

Limitations

We could not calculate exposure (ie, number of injuries/1000 exposure hours) and therefore incidence because we did not prospectively record participant time spent in practices and games during the 3 months after RTP. We assume but do not know that the injuries were physician diagnosed, and we did not obtain time loss from sport due to the injuries. The sample size was reduced due to COVID-19 causing the trial to end early; there was attrition as participants dropped out as they recovered, and there was an unequal loss to follow-up between the groups. Our results require confirmation in adequately powered trials; however, restriction from aerobic activity is no longer standard of care, so it may be challenging to replicate this design in future trials. Clinical recovery definition was standardized across sites, but the Berlin Concussion in Sport Group graduated RTP process was participant specific. Nevertheless, we have no reason to believe that this introduced systematic bias into the trial. The follow-up period in the original trial was limited to 4 months from injury, and it is possible that the results would be different had we followed participants for 1 year. We found no group difference in the rate of subsequent SRC because of the rare occurrence (1 in each group). There was no significant difference in the rates of return to school, sport, or to exercise because most adolescents (approximately 90%) had returned to preinjury participation levels by 4 months. Finally, participants were predominantly white adolescents recruited from hospital- and community-based sports medicine concussion treatment centers, and therefore, our results may not apply to other patient groups (races, younger children, adults) or to other settings.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study suggest that clinicians should prescribe individualized targeted HR aerobic exercise treatment within 10 days of SRC to adolescent athletes to reduce their risk of MSK injury within the 3 months after their clinical recovery and unrestricted RTS, which is when the risk of postconcussion MSK injury is greatest. Aerobic exercise activities early after SRC may reduce subsequent MSK injury risk by functioning as low-level forms of habituation/rehabilitation to help prevent the decline in autonomic, vestibular, and/or oculomotor function that is frequently seen after SRC. Further research on the types and amounts of aerobic exercise that reduce subsequent risk of concussion and MSK injury, and potential mechanisms of action in both sexes, is warranted. Furthermore, future work should compare NTP methods with aerobic exercise interventions for injury reduction to determine which interventions are most effective, and a better understanding is needed of how injury risk is affected by aerobic exercise during the year after injury.

References